6. Technological shift and labour markets

KAT.TAL.322 Advanced Course in Labour Economics

Labour market of educated workers

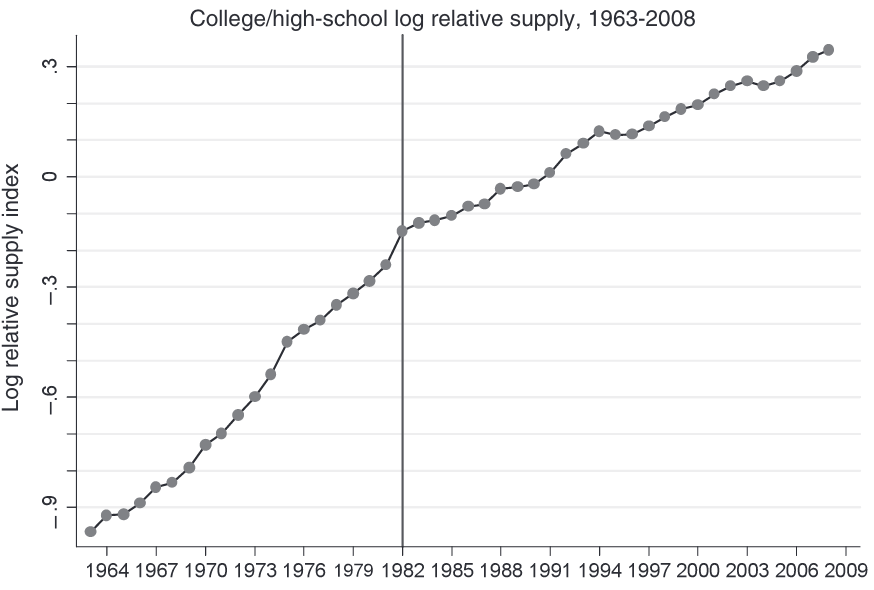

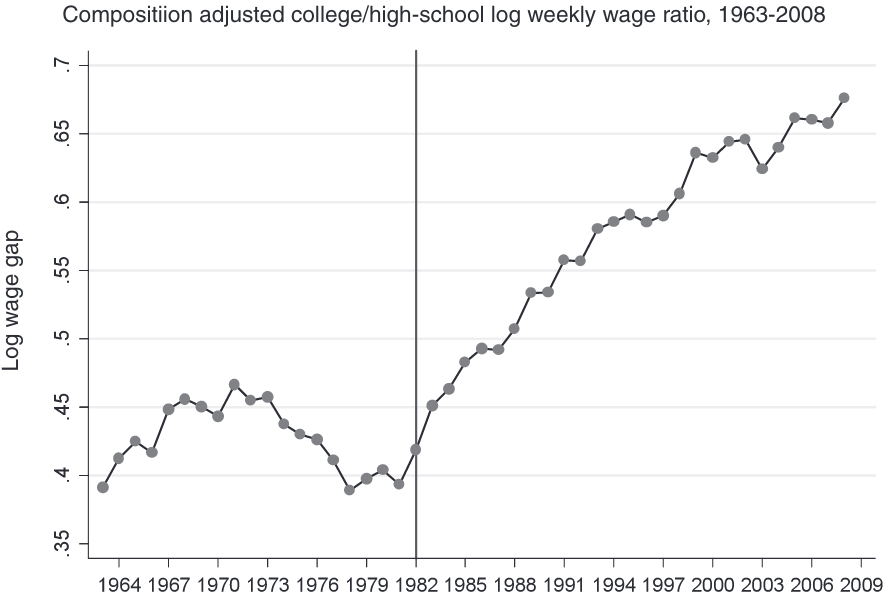

Labour supply of educated workers relative to uneducated is on the rise

Standard theory predicts that their wages should go down.

In fact, we see the opposite \(\Rightarrow\) need to develop new theory

Technological change and the labour market

This lecture is based on Acemoglu and Autor (2011)

Canonical model

Canonical model

Overview

Two types of labour: high- and low-skill

Typically, high edu and low edu (can be relaxed)Skill-biased technological change (SBTC)

New technology disproportionately \(\uparrow\) high-skill labour productivityHigh- and low-skill are imperfectly substitutable

Typically, CES production function with elasticity of substitution \(\sigma\)Competitive labour market

Canonical model

Production function

\[ Y = \left[\left(A_L L\right)^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} + \left(A_H H\right)^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\right]^\frac{\sigma}{\sigma - 1} \]

\(A_L\) and \(A_H\) are factor-augmenting technology terms

\(\sigma \in [0, \infty)\) is the elasticity of substitution

- \(\sigma > 1\) gross substitutes

- \(\sigma < 1\) gross complements

- \(\sigma = 0\) perfect complements (Leontieff production)

- \(\sigma \rightarrow \infty\) perfect substitutes

- \(\sigma = 1\) Cobb-Douglas production

Technological changes do not directly replace skills

Whether \(\uparrow A_H\) increases or decreases labour demand for \(H\) and \(L\) depends on \(\sigma\)

Canonical model

Interpretations

- There is only one good and \(H\) and \(L\) are imperfect substitutes in production

- There are two goods \(Y_H = A_H H\) and \(Y_L = A_L L\) and consumers have CES utility \(\left[Y_L^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} + Y_H^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\right]^\frac{\sigma}{\sigma - 1}\)

- Combination of the two: different sectors produce goods that are imperfect substitutes and \(H\) and \(L\) are employed in both sectors.

Canonical model

Equilibrium wages

\[ \begin{align} w_L &= A_L^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} \left[A_L^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} + A_H^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\left(\frac{H}{L}\right)^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\right]^\frac{1}{\sigma - 1}\\ w_H &= A_H^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} \left[A_L^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\left(\frac{H}{L}\right)^{-\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}} + A_H^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\right]^\frac{1}{\sigma - 1} \end{align} \]

Comparative statics:

\(\frac{\partial w_L}{\partial H/L} > 0\) low-skill wage rises with \(\frac{H}{L}\)

\(\frac{\partial w_H}{\partial H/L} < 0\) high-skill wage falls with \(\frac{H}{L}\)

\(\frac{\partial w_i}{\partial A_L} > 0\) and \(\frac{\partial w_i}{\partial A_H} > 0, ~\forall i \in \{L, H\}\) both wages rise with \(A_L\) and \(A_H\)

Canonical model

Tinbergen’s race in the data

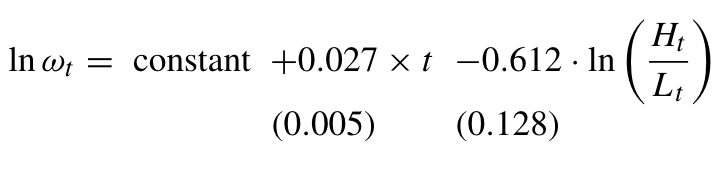

Katz and Murphy (1992)

The log-equation of skill premium is extremely attractive for empirical analysis

\[ \ln\frac{w_{H, t}}{w_{L, t}} = \frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} \ln\left(\frac{A_{H, t}}{A_{L, t}}\right) -\frac{1}{\sigma} \ln \left(\frac{H_t}{L_t}\right) \]

Assume a log-linear trend in relative productivities

\[ \ln \left(\frac{A_{H, t}}{A_{L, t}}\right) = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 t \]

and plug it into the log skill premium equation:

\[ \ln\frac{w_{H, t}}{w_{L, t}} = \frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\alpha_0 + \frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} \alpha_1 t -\frac{1}{\sigma} \ln\left(\frac{H_t}{L_t}\right) \]

Tinbergen’s race in the data

Katz and Murphy (1992)

Estimated the skill premium equation using the US data in 1963-87

Implies elasticity of substitution \(\sigma \approx \frac{1}{0.612} =\) 1.63

Agrees with other estimates that place \(\sigma\) between 1.4 and 2 (Acemoglu and Autor 2011)

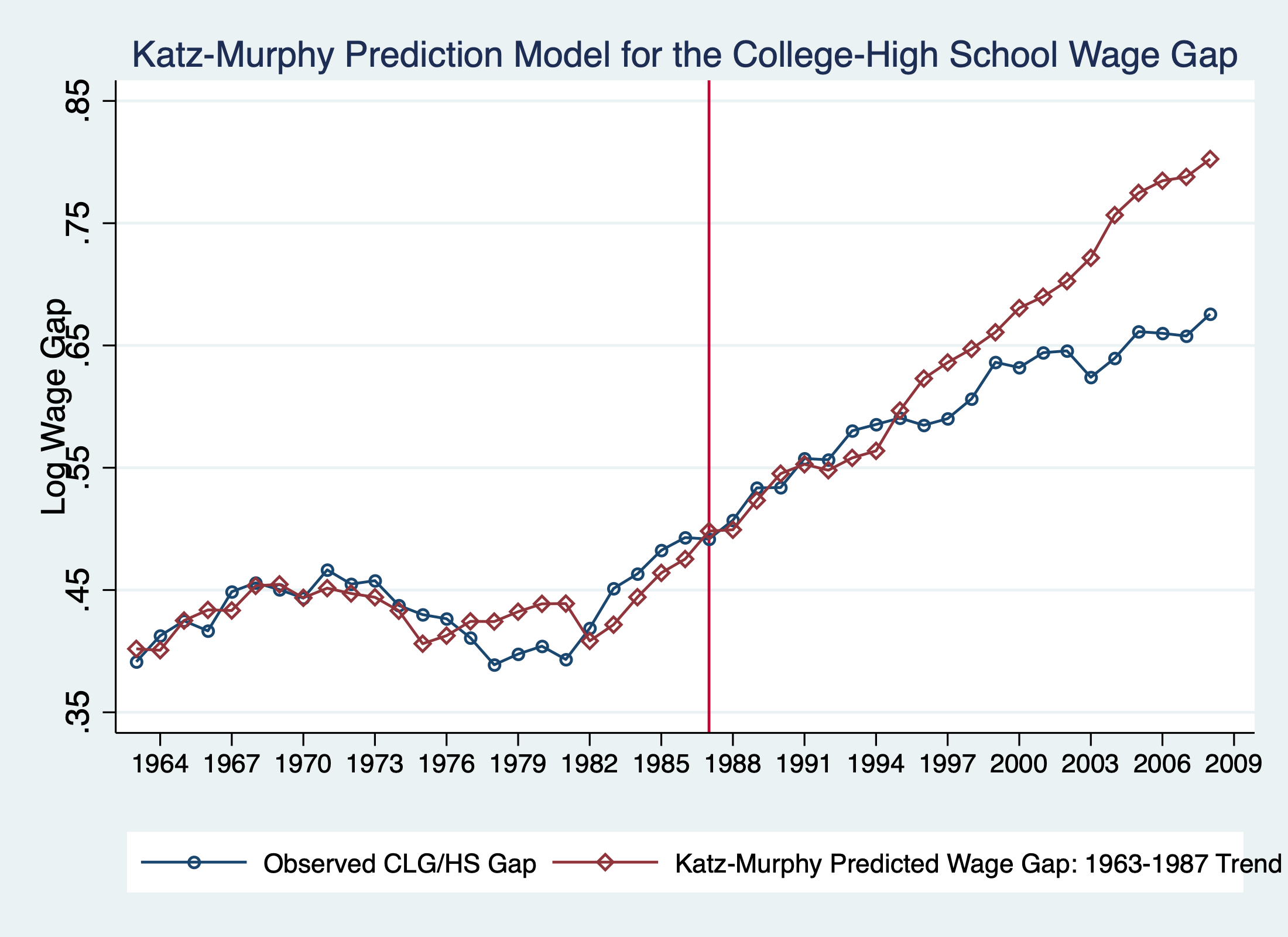

Tinbergen’s race in the data

Very close fit up to mid-1990s, diverge later

Fit up to 2008 implies \(\sigma \approx\) 2.95

Accounting for divergence:

non-linear time trend in \(\ln\frac{A_H}{A_L}\)

brings \(\sigma\) back to 1.8, but implies \(\frac{A_H}{A_L}\) slowed downdifferentiate labour by age/experience as well

Highlight that slowdown of tech progress in 1990s and 2000s is a very hard sell

Canonical model

Summary

- Simple link between wage structure and technological change

- Attractive explanation for college/no college wage inequality1

- Average wages \(\uparrow\) (follows from \(\partial w_i / \partial A_H\) and \(\partial w_i/ \partial A_L\))

However, the model cannot explain other trends observed in the data:

- Falling \(w_L\)

- Earnings polarization

- Job polarization

Also silent about endogeneous adoption or labour-replacing technology.

Unexplained trend: falling real wages

The only way that canonical model can explain falling real wages is if

\(L\) was over-abundant (not the case)

\(\downarrow A_L\) or \(\downarrow A_H\), i.e., technological regress (not the case)

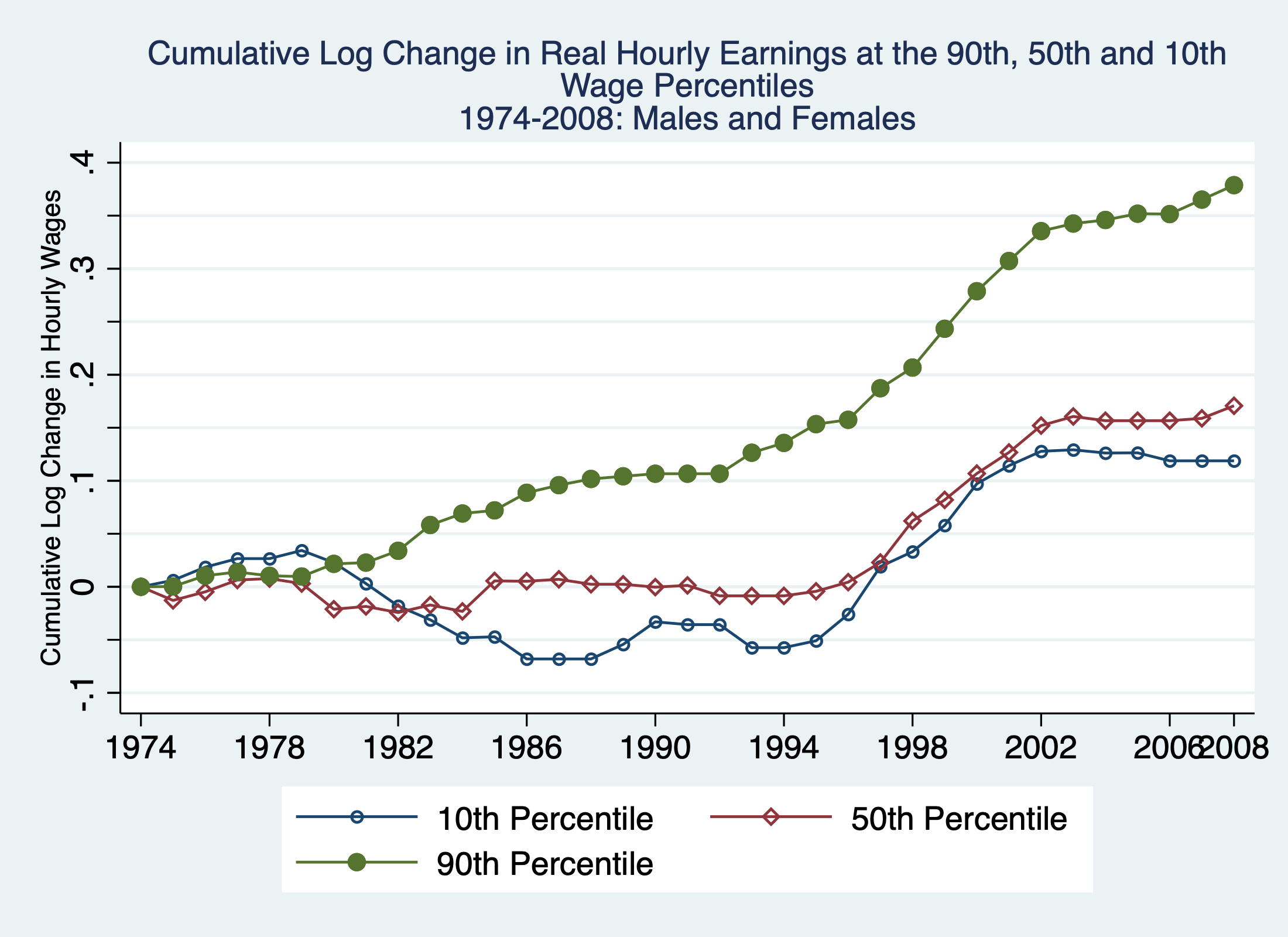

Unexplained trend: earnings polarization

The canonical model can explain between group inequality, like college vs non-college workers

But it suggests that within-group inequality in either group moves 1-to-1 with skill premium.

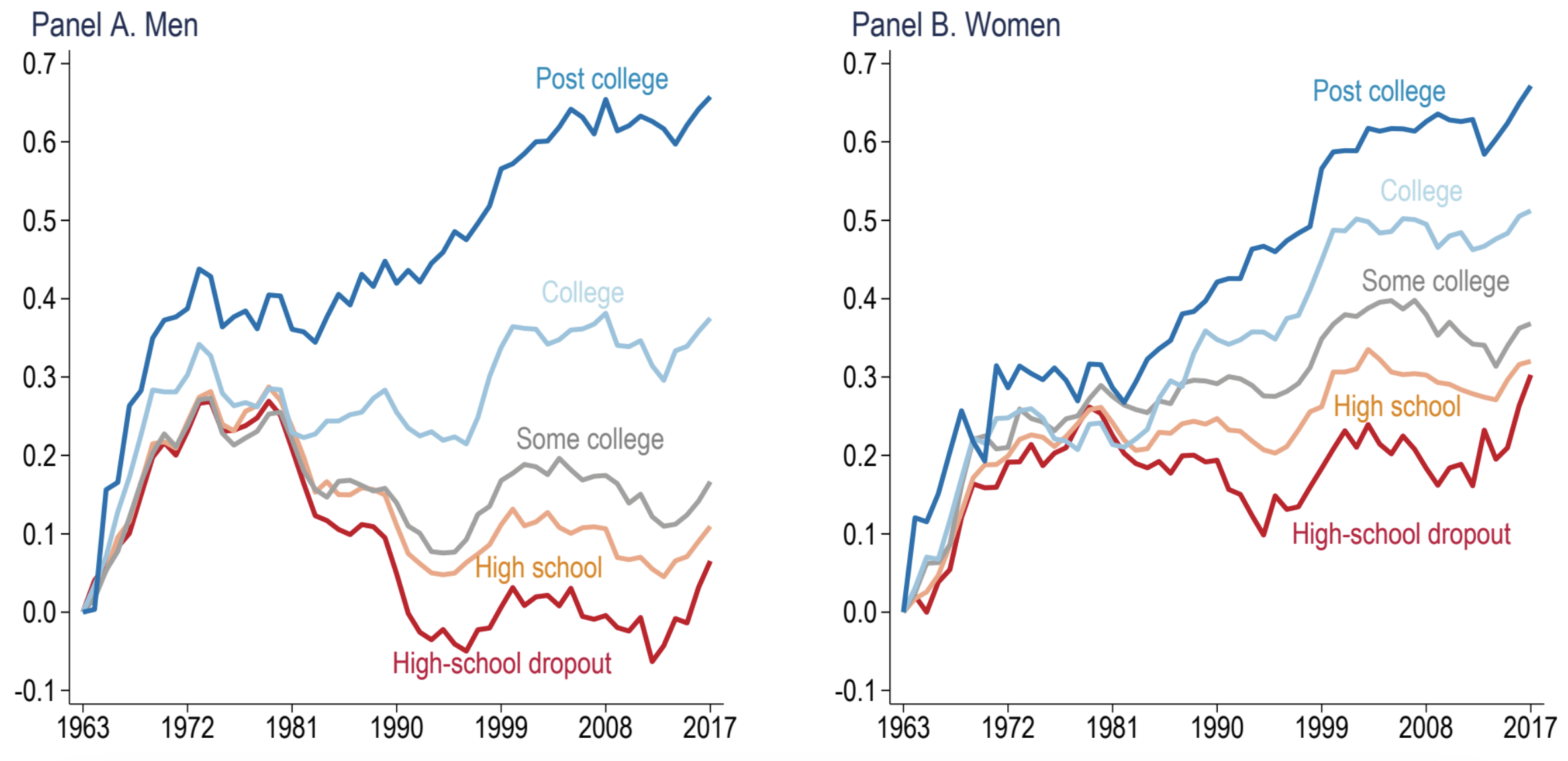

This graph implies that within-group inequalities moved at their own paces.

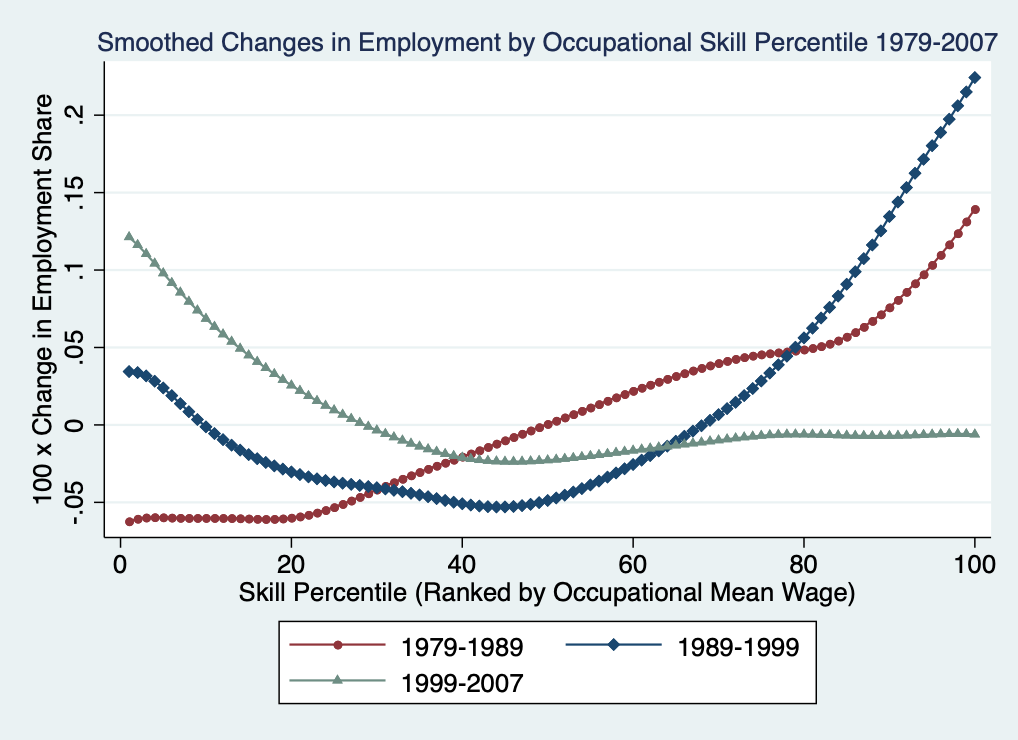

Unexplained trend: job polarization

This is just simple, there is absolutely no notion of occupations in the canonical model.

So, no instrument to think about mid-skill mid-job people.

Task-based model

Task-based model

Overview

Task is a unit of work activity that produces output

Skill is a worker’s endowment of capabilities for performing tasks

Key features:

- Tasks can be performed by various inputs (skills, machines)

- Comparative advantage over tasks among workers

- Multiple skill groups

- Consistent with canonical model predictions

Canonical model is a special case: task = skill

Occupations = bundles of tasks

At least 3 skill groups to study earnings polarization

Task-based model

Production function

Unique final good \(Y\) produced by continuum of tasks \(i \in [0, 1]\)

\[ Y = \exp \left[\int_0^1 \ln y(i) \text{d}i\right] \]

Three types of labour: \(H\), \(M\) and \(L\) supplied inelastically.

\[ y(i) = A_L \alpha_L(i) l(i) + A_M \alpha_M(i) m(i) + A_H \alpha_H(i) h(i) + A_K \alpha_K(i) k(i) \]

\(A_L, A_M, A_H\) are factor-augmenting technologies

\(\alpha_L(i), \alpha_M(i), \alpha_H(i)\) are task productivity schedules

\(l(i), m(i), h(i)\) are number of workers by types allocated to task \(i\)

Price of final good is the numeraire \(\Rightarrow \max Y - wL\)

There is now capital in the production function, but no comparative statics about it.

\(\alpha\) terms describe how productive different types are in producing task \(i\)

Hence, each task can be produced by \(L\), \(M\) and \(H\), but their comparative advantages are in that task are different!

Task-based model

Market clearing conditions

\[ \int_0^1 l(i) \text{d}i \leq L \qquad \int_0^1 m(i) \text{d}i \leq M \qquad \int_0^1 h(i) \text{d}i \leq H \]

In what follows, we assume machines play no role \(\alpha_K(\cdot) = 0\). See Acemoglu and Restrepo (2018) for a more complete model where tasks can be performed by machines and production function features imperfect substitution between inputs.

Higher task index \(i\) correspond to more complex task in which \(H\) is better than \(M\) is better than \(L\).

Task-based model

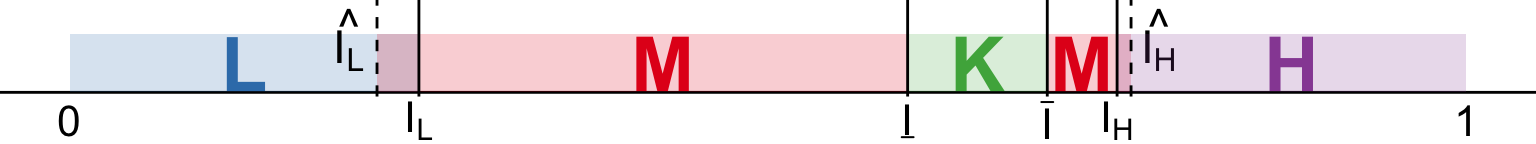

Equilibrium without machines

Note that boundaries \(I_L\) and \(I_H\) are endogenous

This gives rise to the substitution of skills across tasks

Endogenous boundaries means that they will change when

relative supply of skills changes or

technology changes.

Task-based model

Law of one wage

Output price is normalised to 1 \(\Rightarrow \exp\left[\int_0^1 \ln p(i) \text{d}i\right] = 1\)

All tasks employing a given skill pay corresponding wage

\[ \begin{align} w_L &= \frac{A_L \alpha_L(i)}{p(i)} &\Rightarrow& \qquad l(i) &=& \frac{L}{I_L} &\forall& i < I_L \\ w_M &= \frac{A_M \alpha_M(i)}{p(i)} &\Rightarrow& \qquad m(i) &=& \frac{M}{I_H - I_L} &\forall& I_L < i < I_H \\ w_H &= \frac{A_H \alpha_H(i)}{p(i)} &\Rightarrow& \qquad h(i) &=& \frac{H}{1 - I_H} &\forall& i > I_H \end{align} \]

Task-based model

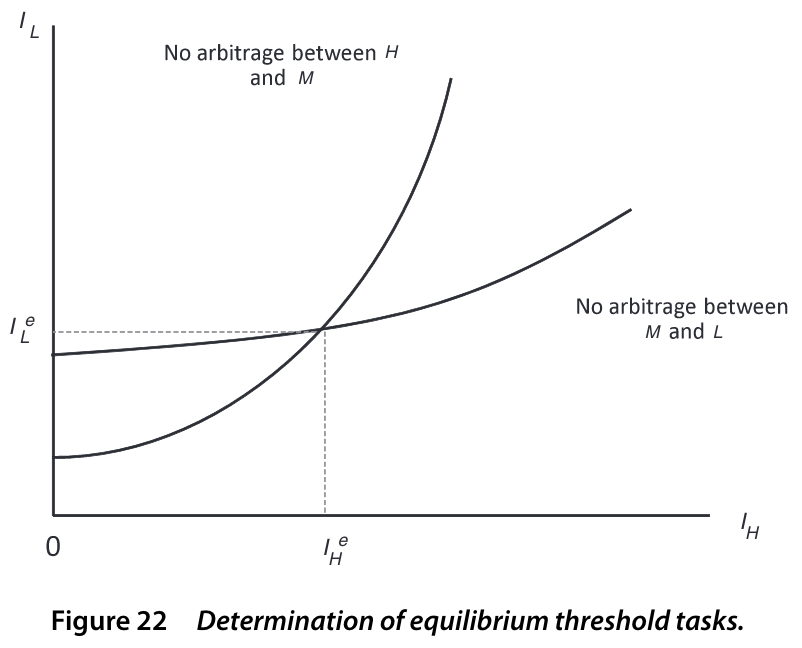

Endogenous thresholds: no arbitrage

Threshold task \(I_H\): equally profitable to produce with either \(H\) or \(M\) skills

\[ \frac{A_M \alpha_M(I_H) M}{I_H - I_L} = \frac{A_H \alpha_H(I_H) H}{1 - I_H} \]

Similarly, for \(I_L\):

\[ \frac{A_L \alpha_L(I_L) L}{I_L} = \frac{A_M \alpha_M(I_L) M}{I_H - I_L} \]

Task-based model

Endogenous thresholds: no arbitrage

The equilibrium at the intersection because that’s when firm has no incentive to use \(M\) for either of \(L\) or \(H\) tasks. Consider another point along H-M curve: firm is still indifferent between \(H\) and \(M\) for \(I_H\) task. But there will be arbitrage where \(M\) could be more profitable for \(I_L\) task (or \(L\)).

Task-based model

Comparative statics: wage elasticities

\[ \begin{matrix} \frac{\text{d} \ln w_H / w_L}{\text{d}\ln A_H} > 0 & \frac{\text{d} \ln w_M / w_L}{\text{d}\ln A_H} < 0 & \frac{\text{d} \ln w_H / w_M}{\text{d}\ln A_H} > 0 \\ \frac{\text{d} \ln w_H / w_L}{\text{d}\ln A_M} \lesseqqgtr 0 & \frac{\text{d} \ln w_M / w_L}{\text{d}\ln A_M} > 0 & \frac{\text{d} \ln w_H / w_M}{\text{d}\ln A_M} < 0 \\ \frac{\text{d} \ln w_H / w_L}{\text{d}\ln A_L} < 0 & \frac{\text{d} \ln w_M / w_L}{\text{d}\ln A_L} < 0 & \frac{\text{d} \ln w_H / w_M}{\text{d}\ln A_L} > 0 \end{matrix} \]

Consider \(\uparrow A_M\):

- \(M\) more productive \(\Rightarrow ~ \uparrow\) set of medium-skill tasks \(\uparrow I_H\) and/or \(\downarrow I_L\)

- Since supply is constant, \(\uparrow w_M\) and \(\downarrow w_H, w_L\)

- Depending on comparative advantages:

- \(\left|\beta^\prime_L(I_L) I_L\right| > \left|\beta^\prime_H(I_H)(1 - I_H)\right| \Rightarrow \frac{w_H}{w_L} \downarrow\)

- \(\left|\beta^\prime_L(I_L) I_L\right| < \left|\beta^\prime_H(I_H)(1 - I_H)\right| \Rightarrow \frac{w_H}{w_L} \uparrow\)

3a corresponds to when \(L\) have much stronger comparative advantage relative to \(M\) below \(I_L\)

3b on the contrary is when \(H\) have much stronger advantage above \(I_H\) than do \(L\) below \(I_L\).

When \(A_H \uparrow\), \(H\) displaces \(M\) directly. There is indirect effect that \(M\) displaces \(L\), but the indirect effect is small!

Unlike canonical model, changes in \(A\) terms can reduce relative wages! More than that, it is also possible to show they reduce absolute levels of wages too (Wage effects in subsection 4.4)

Task-based model

Task replacing technologies

Assume in \([\underline{I}, \bar{I}] \subset [I_L, I_H]\) machines outperform \(M\)2. Otherwise, \(\alpha_K(i) = 0\).

In this case,

- \(w_H / w_M\) increases

- \(w_M / w_L\) decreases

- \(w_H / w_L \uparrow \color{#9a2515}{\left(\downarrow\right)}\) if \(\left|\beta^\prime_L(I_L) I_L\right| \stackrel{<}{\color{#9a2515}{>}} \left|\beta^\prime_H(I_H)(1 - I_H)\right|\)

- Machines replace \(M \Rightarrow\) demand for \(M \downarrow \Rightarrow w_M \downarrow\)

- Even though thresholds move such that \(I_\hat{H} - I_\hat{L} > I_H - I_L\), the expansion is not large enough to compensate for \(K\) region (I think)

- Then, displaced \(M\) can either take up some more tasks that were previously done by \(L\) or \(H\), but overall demand for \(M\) is down.

- Whether or not the displacement is heavier on \(L\) boundary or \(H\) boundary depends on comparative advantages.

- Assuming that displacement is larger \(L\) boundary, also demand for \(L\) falls, hence \(w_H/w_L\) rises!

Task-based model

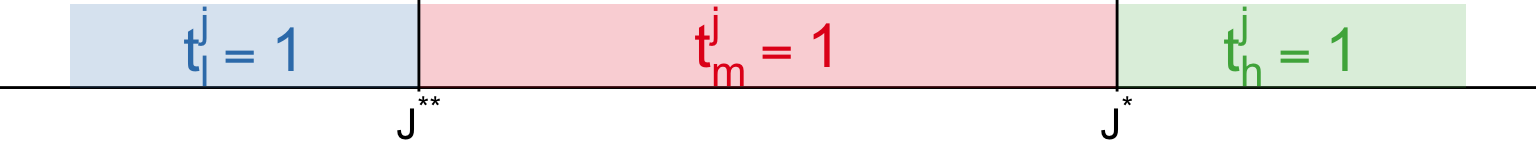

Endogenous supply of skills

Each worker \(j\) is endowed with some amount of each skill \(l^j, m^j, h^j\)

Workers allocate time to each skill given

\[ \begin{align} &t_l^j + t_m^j + t_h^j \leq 1 \\ &w_L t_l^j l^j + w_M t_m^j m^j + w_H t_h^j h^j \end{align} \]

Assuming that \(\frac{h^j}{m^j}\) and \(\frac{m^j}{l^j}\) are decreasing in \(j\), there exist \(J^\star\left(\frac{w_H}{w_M}\right)\) and \(J^{\star\star}\left(\frac{w_M}{w_L}\right)\)

Comparative statics are more complicated!

But assume that similar to firms pushing \(M\) workers to old \(L\) tasks on the margin, workers too are more elastic at \(J^\star\) than \(J^{\star\star}\).

Then, the total effect is even stronger for \(\downarrow M\) because less demand from firms and less supply from workers. The effect on \(w_M\) is ambiguous.

However, can’t get nice clean predictions when supply and demand move in different directions.

Task-based model

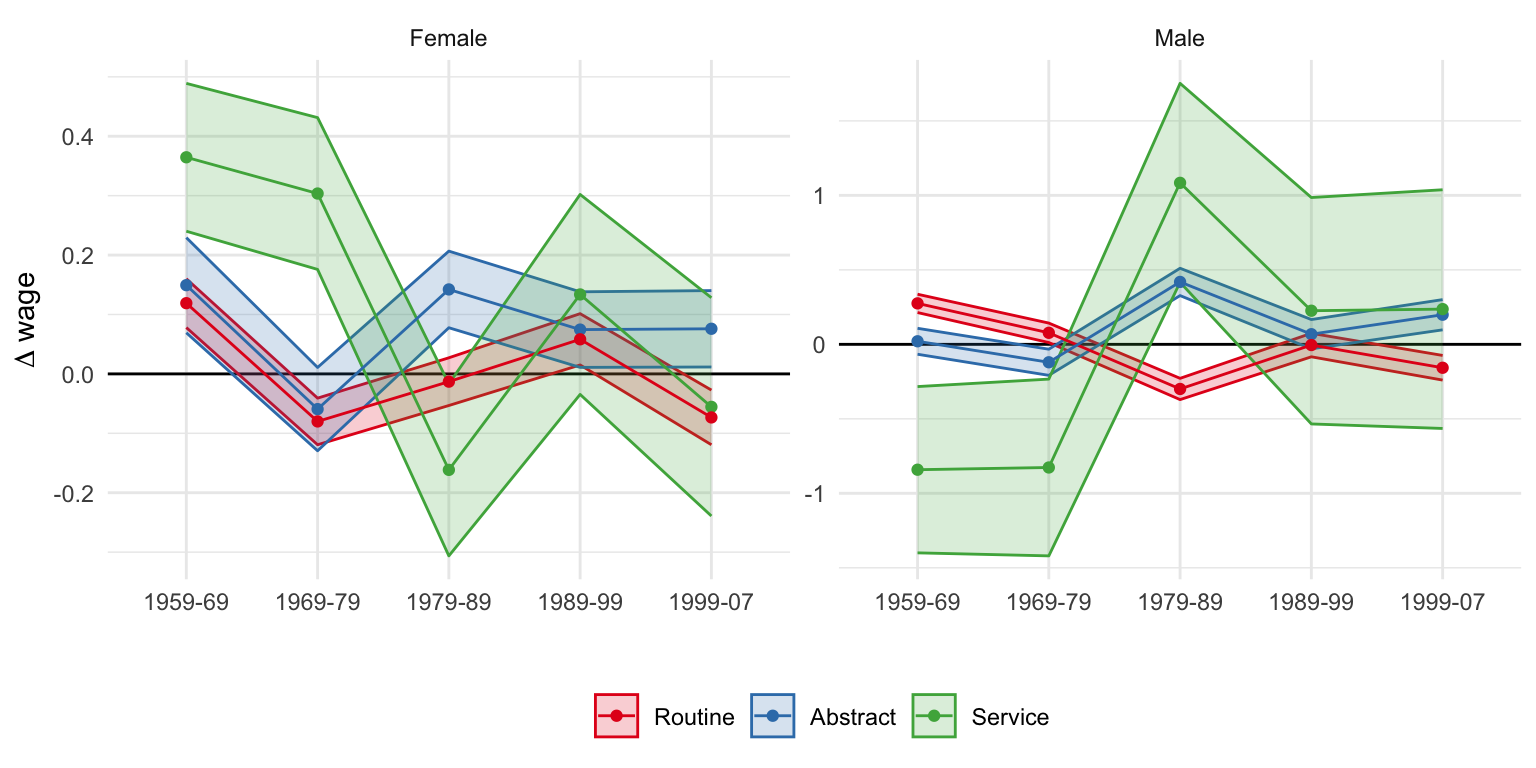

Illustration in the data

Suppose \(A_H \uparrow\). The model predicts that \(\frac{w_H}{w_M} \uparrow\) and \(\frac{w_M}{w_L} \downarrow\).

Use occupational specialization at some \(t = 0\) as comparative advantage.

- \(\gamma_{sejk}^i\) share of 1959 population employed in \(i\) occupations, \(\forall i \in \{H, M, L\}\)

\[ \Delta w_{sejk\tau} = \sum_t \left[\beta_t^H \gamma_{sejk}^H + \beta_t^L \gamma_{sejk}^L\right] 1\{\tau = t\} + \delta_\tau + \phi_e + \lambda_j + \pi_k + e_{sejk\tau} \]

Descriptive regression informed by the model!

Stress that since \(H\) is now doing some of what \(M\) used to do, wages per those tasks \(\uparrow\) because \(H\) does it more productively now than \(M\) used to do!

However, \(w_M \downarrow\) because the skill group does less overall.

Wages per task can move in opposite direction than wages per skill!

\(s\) - gender, \(e\) - education, \(j\) - age group, \(k\) - region.

\[ \gamma_{sejk}^H + \gamma_{sejk}^M + \gamma_{sejk}^L = 1 \]

\(\tau\) - decade

Task-based model

Illustration in the data

Stress again that this is descriptive!

Task-based model

Summary

- A rich model that can accommodate numerous scenarios

- Outsourcing tasks to lower-cost countries

- Endogenous technological change

- Creation of new tasks

- Useful tool to study effect on inequality and job polarization

Empirical results

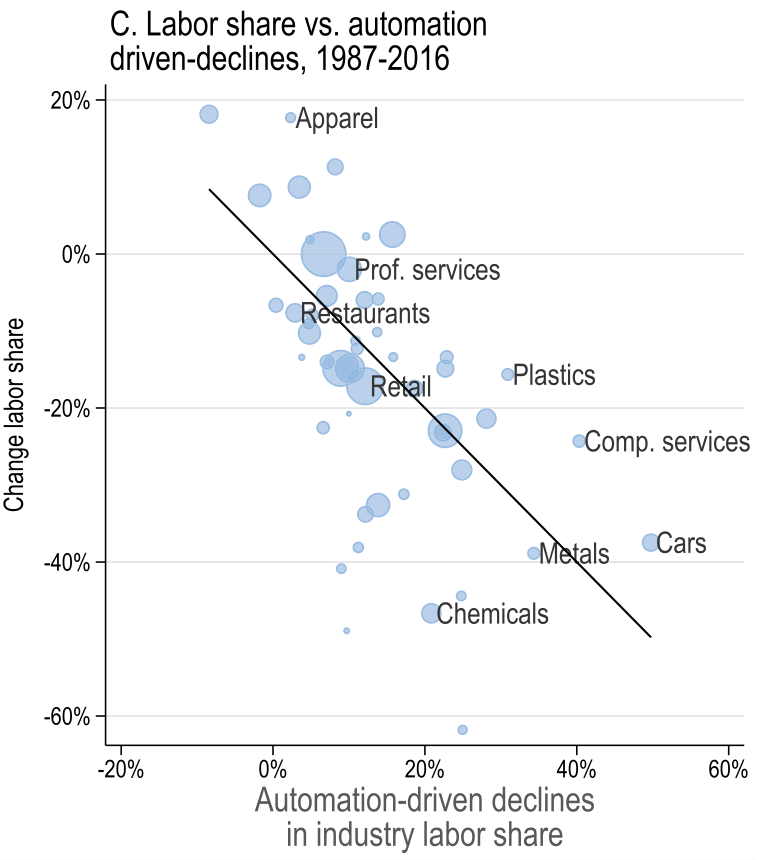

Acemoglu and Restrepo (2022)

Environment

Multi-sector model with imperfect substitution between production inputs

\[ \text{Task displacement}_g^\text{direct} = \sum_{i \in \mathcal{I}} \omega_g^i \frac{\omega_{gi}^R}{\omega_i^R} \left(-d \ln s_i^{L, \text{auto}}\right) \]

\(\omega_g^i\) - share of wages earned by worker group \(g\) in industry \(i\)

(exposure to industry \(i\))\(\frac{\omega_{gi}^R}{\omega_i^R}\) - specialization of group \(g\) in routine tasks \(R\) within industry \(i\)

\(-d \ln s_i^{L, \text{auto}}\) - % decline in industry \(i\)’s labour share due to automation

attribute 100% of the decline to automation

predict given industry adoption of automation technology

Like in simple exercise, specialization is measured at some \(t_0\), which here is 1980. So, relative occupation shares in a demographic group “describe” their comparative advantage in that group.

The changes are computed over 1987-2016.

Acemoglu and Restrepo (2022)

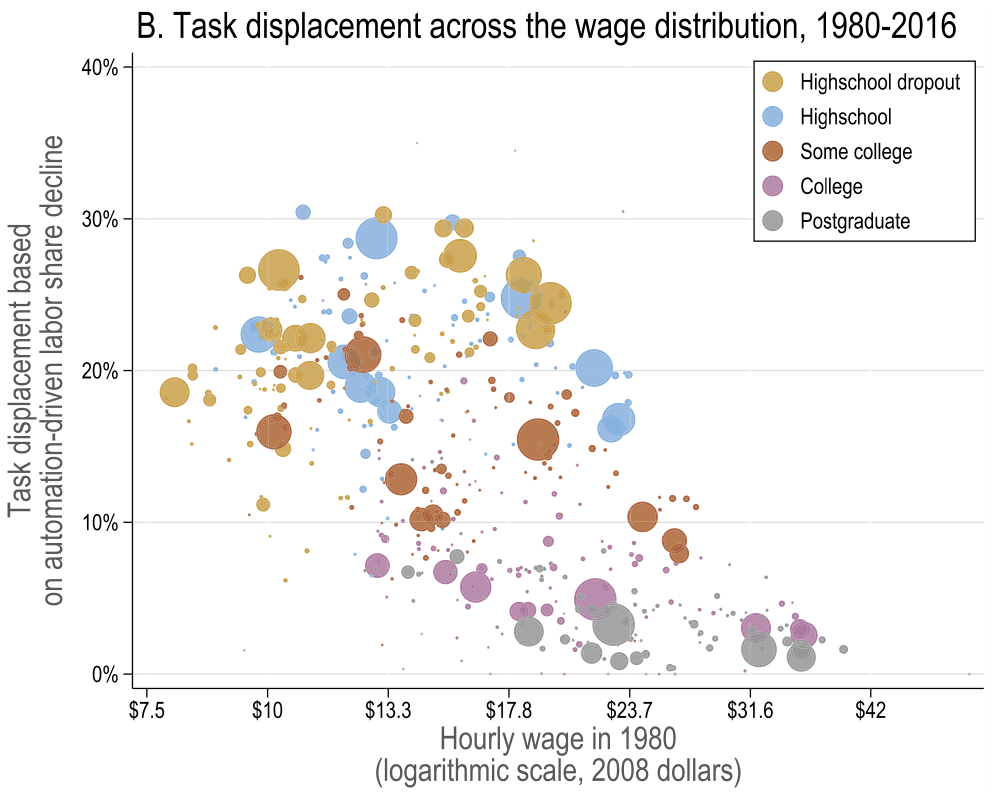

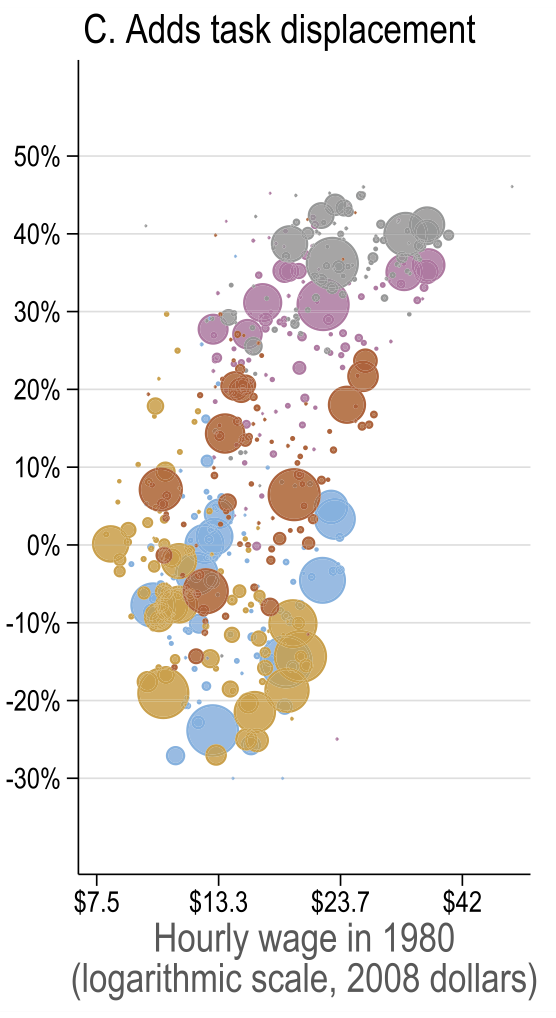

Task displacement

- Lower educated groups saw up to 30% decline in their task shares!

- The displacement vs initial wage is inverse-U shaped => most of the displacement happened towards the middle

Acemoglu and Restrepo (2022)

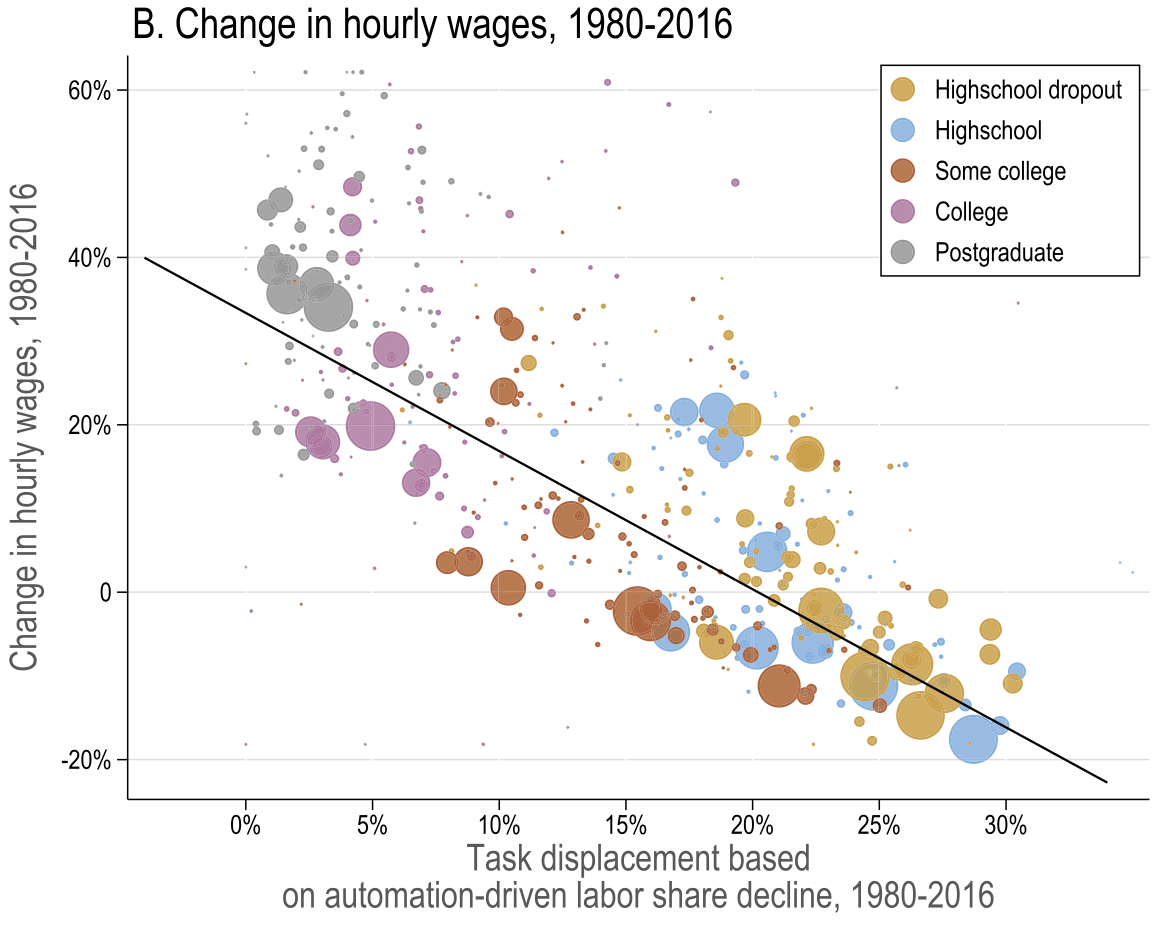

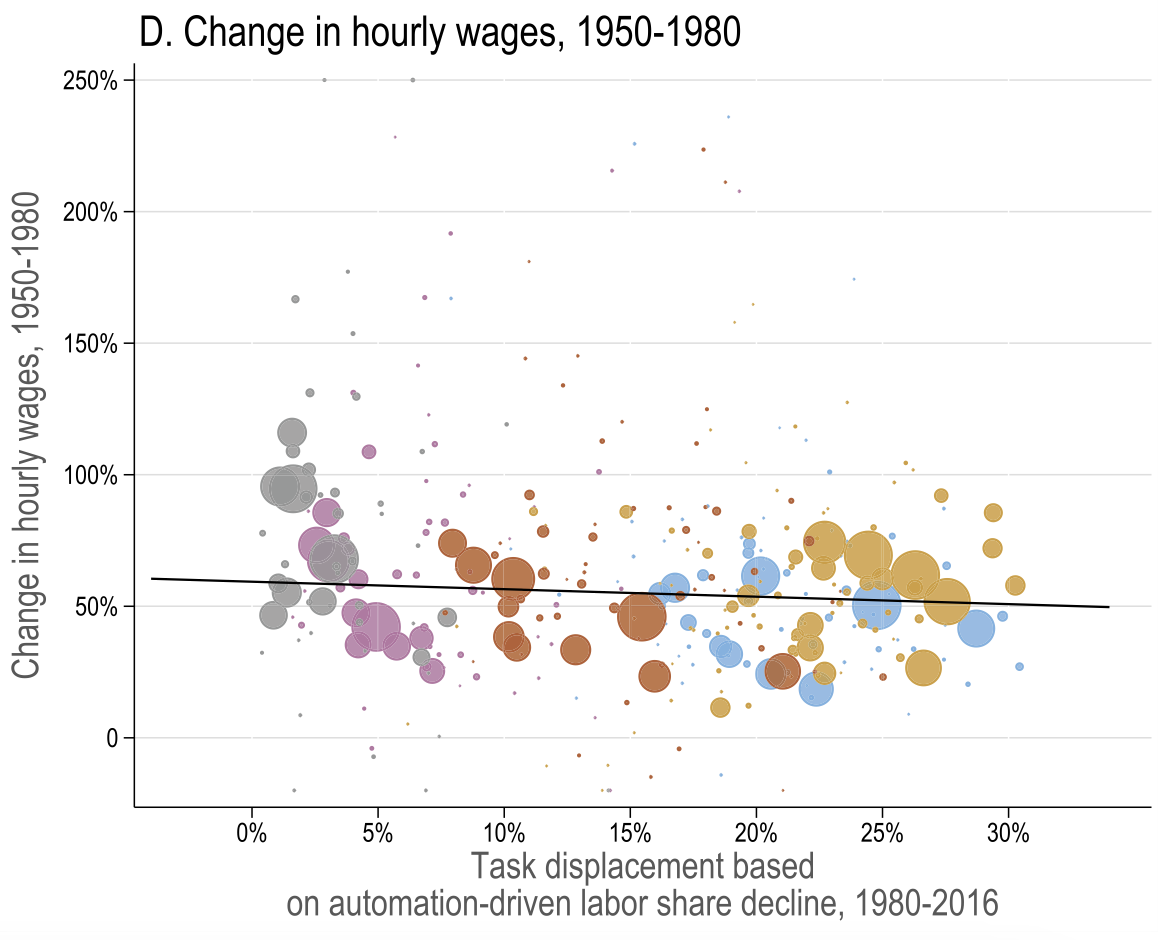

Task displacement and changes in real wages

They verify these observations in a series of reduced form regressions. In particular,

50-70% of changes in wage structure are linked to task displacement and to a much smaller extent to offshoring

they conclude that SBTC without task displacement explains less of variation in the data

they ruled out alternative channels like

other non-automation capital

increase in capital use intensity

markups

industry concentration

unionization

and import competition

However, the reduced form estimates ignore general equilibrium. That is, it assumes

there is no endogenous adjustment of task thresholds at other margins (ripple effects)

no change in industry composition

doesn’t take into account productivity gains

Acemoglu and Restrepo (2022)

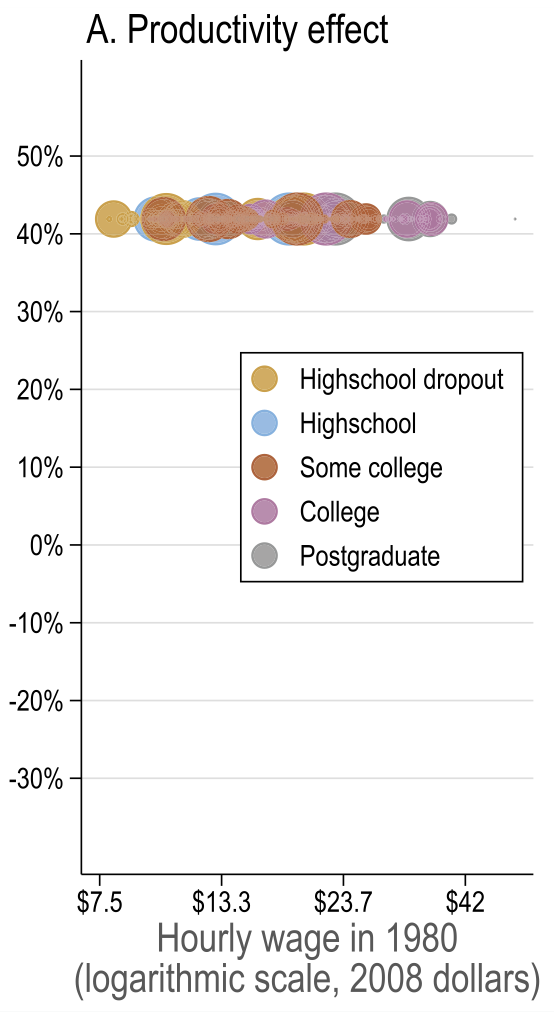

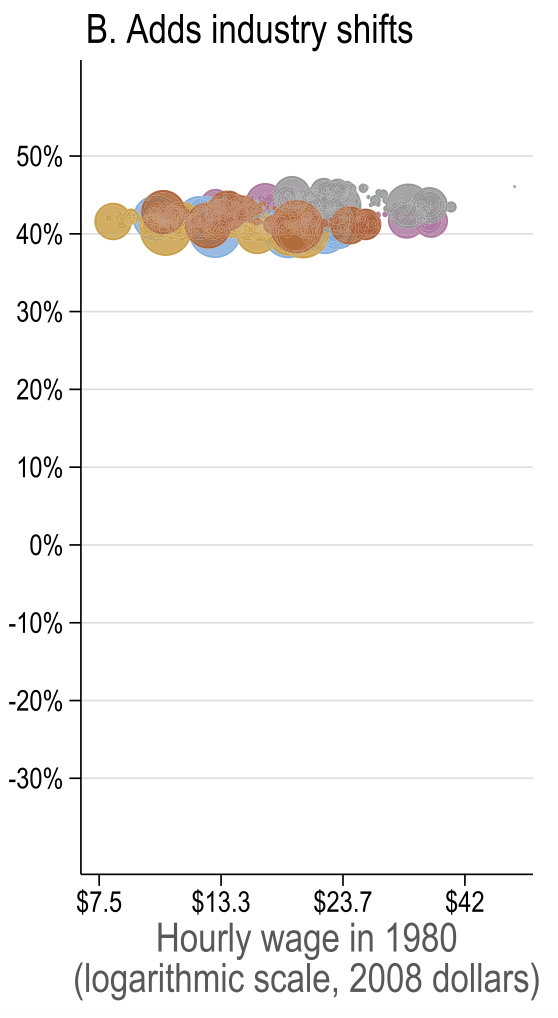

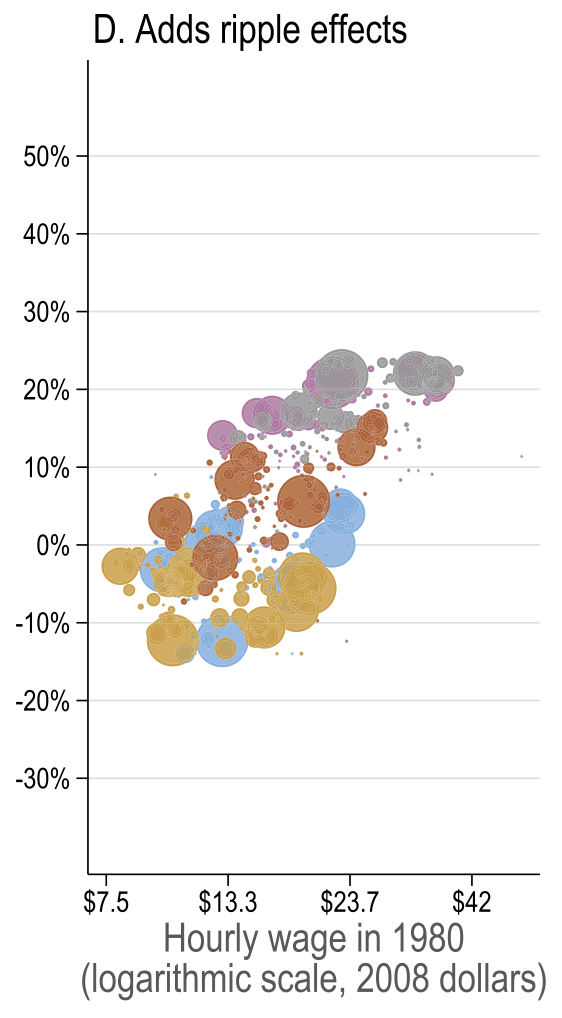

General equilibrium results

Source: Figure 7

- Common productivity effect

It’s when productivity improvement shifts supply of goods upwards meaning that output of firms goes up and as a result firm’s labour demand goes up as well for all labour categories. - Changes in industry composition induced by automation

Automation induces shift towards sectors with less automation, such as services \(\Rightarrow\) demand for workers in those sectors goes up

Account for <7% of observed changes in US wage structure - Direct task displacement

Explains up to 94% of observed changes in US wage structure, higher than reduced form estimates. The direct effect is larger because it does not allow the displaced workers to compete for tasks in other groups. The reduced form estimate did not control for it, hence it picked up some of the ripple effect. - Allowing for ripple effects

As expected, the magnitudes are lower because displaced workers start performing other group tasks and thus spread the effect across groups.

Acemoglu and Restrepo (2022)

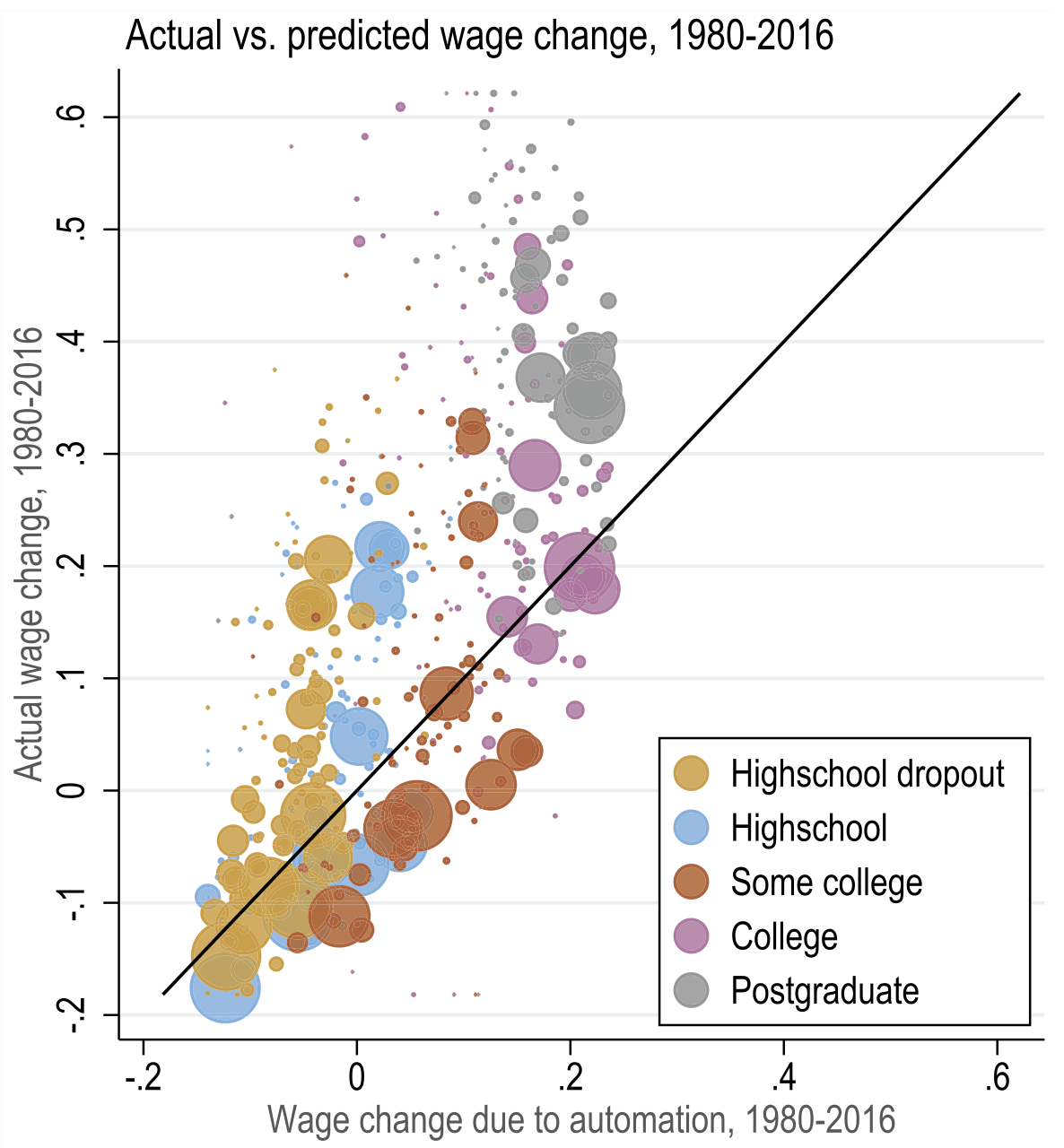

Model fit

The model has close fit to the data everywhere except top of growth distribution

Technology-labour complementarity at the top

Different kinds of jobs (winner-takes-it-all)

Both absent from the model

It also predicts well changes in college premium and wages of men without high school

But it misses big on aggregate things like GDP and TFP

could indicate there were factor-augmenting tech shifts, productivity deepenings, or even new tasks

this wold affect wage levels, but would have little impact on inequality because have shown that inequality is largely attributed to automation

It also suggests that automation-induced investments in the model are in line with data

It also misses on wages of women, which could suggest that supply side ignored so far can also play an important role.

Summary

Two theories linking technological advancements and labour markets

Canonical model (SBTC)

- Simple application of two-factor labour demand theory

- Empirically attractive characterization of between-group inequality

- Fails to account for within-group inequality, polarization, and displacement

Task-based model (automation)

- Rich model linking skills to tasks to output

- Explains large share of changes in the wage structure since 1980s

Next: Labour market discrimination

Also mention that work continues because

adoption is itself an endogenous decision

creation of new tasks

labour supply adjustments

Appendix: derivation of wage equations

The firm problem is to choose entire schedules \(\left(l(i), m(i), h(i)\right)_{i=0}^1\) to

\[ \max PY - w_L L - w_M M - w_H H \]

Consider FOC wrt \(l(j)\):

\[ PY \int_0^1 \frac{1}{y(j)} A_L \alpha_L(j) \text{d}i - w_L \int_0^1 \text{d}i = 0 \]

We normalised \(P = 1\); therefore, the FOC can be rewritten as

\[ \frac{Y}{y(j)} A_L \alpha_L(j) = w_L \]

On the next slide, we see that \(\frac{Y}{y(j)} = \frac{1}{p(j)}\).

Similar argument for \(w_M\) and \(w_H\).

Appendix: derivation of skill allocations

Numeraire price (\(P=1\)) is chosen such that \(\frac{y(i)}{Y} = \frac{p(i)}{P} = p(i), \forall i \in [0, 1]\)

Therefore, productivity of \(L\) is \(\frac{Y}{L} = \frac{y(i)}{p(i)L} = \frac{y(j)}{p(j)L}, \forall i \neq j < I_L\)

If we plug in definition of \(y(i)\) and notice that only \(l(i)\) matters when \(i < I_L\), then

\[ \frac{A_L \alpha_L(i) l(i)}{p(i) L} = \frac{A_L \alpha_L(j)l(j)}{p(j)L} \]

Given the wage equations in Law of one wage, we know \(\frac{A_L\alpha_L(i)}{p(i)} = \frac{A_L \alpha_L(j)}{p(j)}\). Therefore, \(l(i) = l(j), \quad \forall i\neq j < I_L\).

Plug it into the market clearing condition for \(L\)

\[ L = \int_0^{I_L} l(i) \text{d}i = l I_L \quad \Longrightarrow \quad l(i) = l = \frac{L}{I_L}, \forall i < I_L \]

Similar argument for \(m(i)\) and \(h(i)\).