8. Technological shift and labour markets

KAT.TAL.322 Advanced Course in Labour Economics

September 17, 2025

Technological shift and the labour market

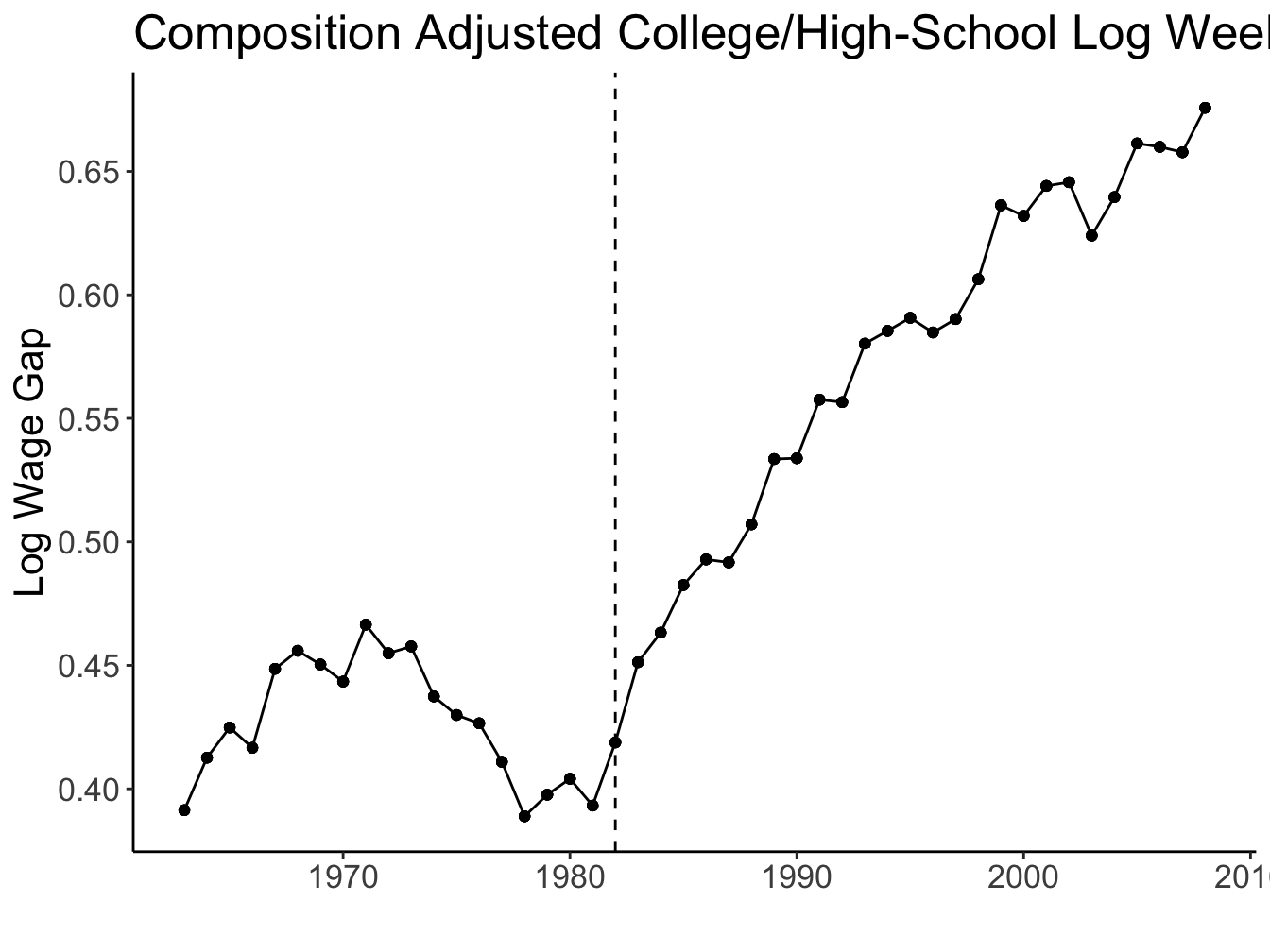

Stylised facts

Labour market of educated workers

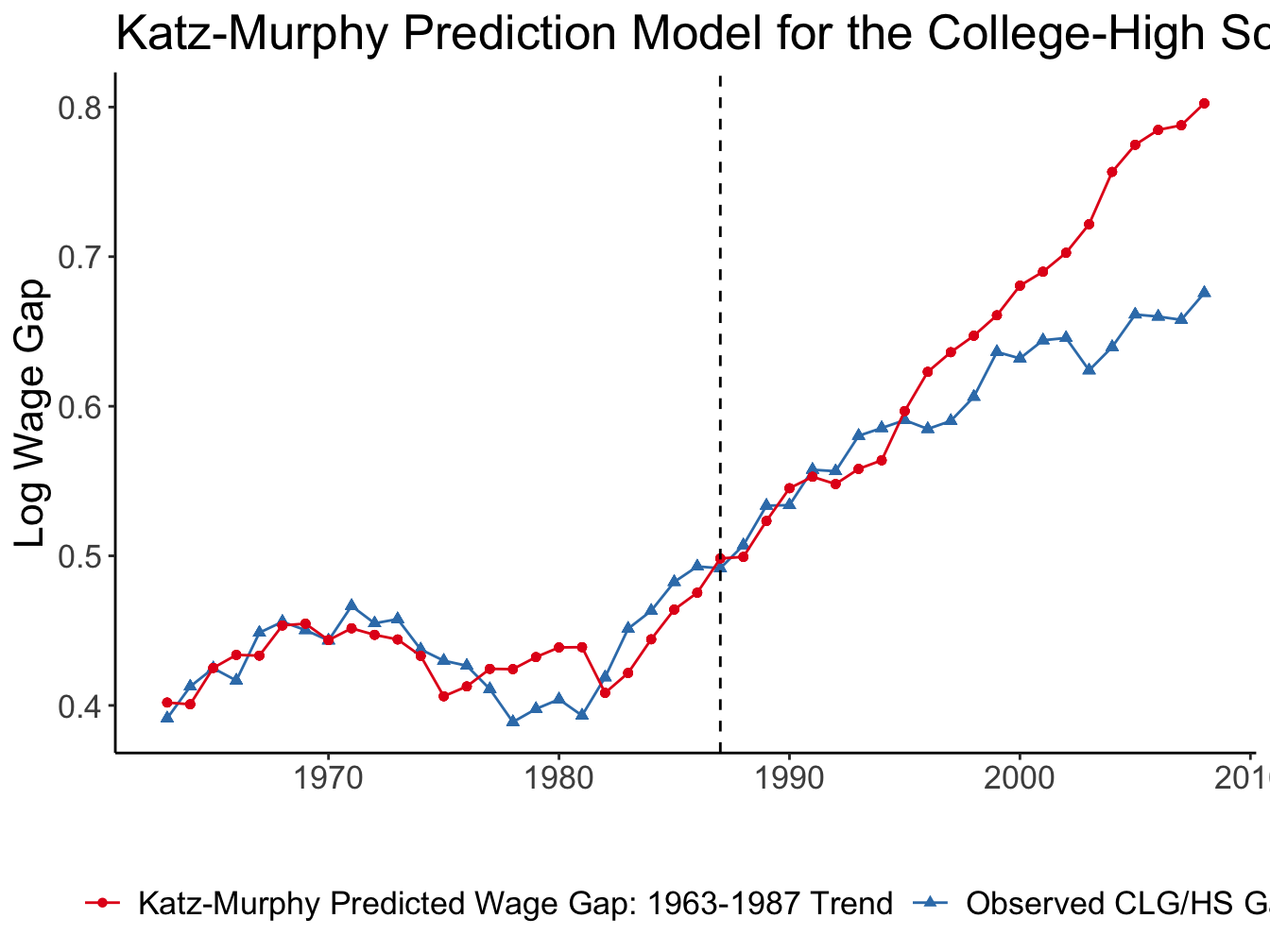

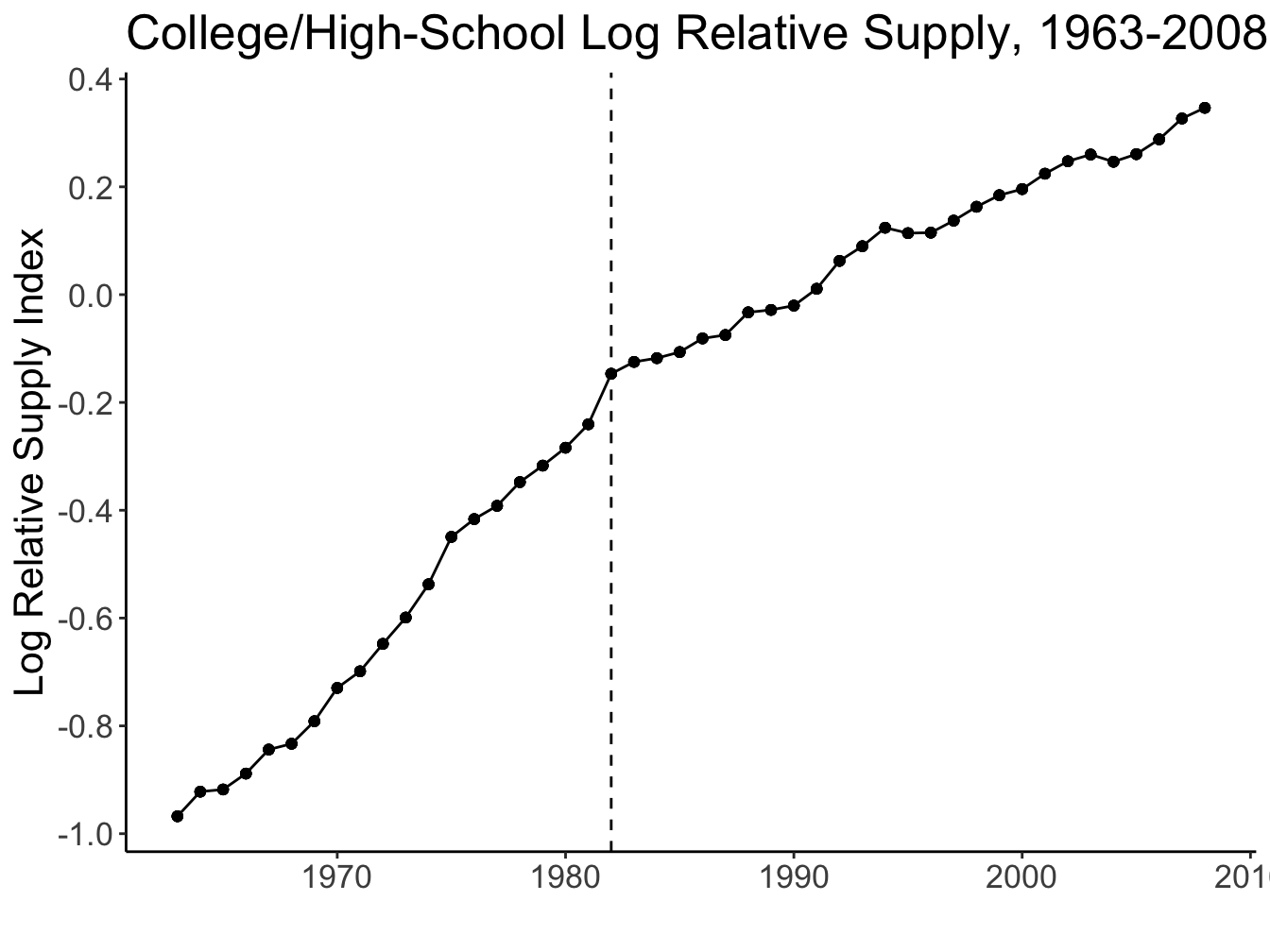

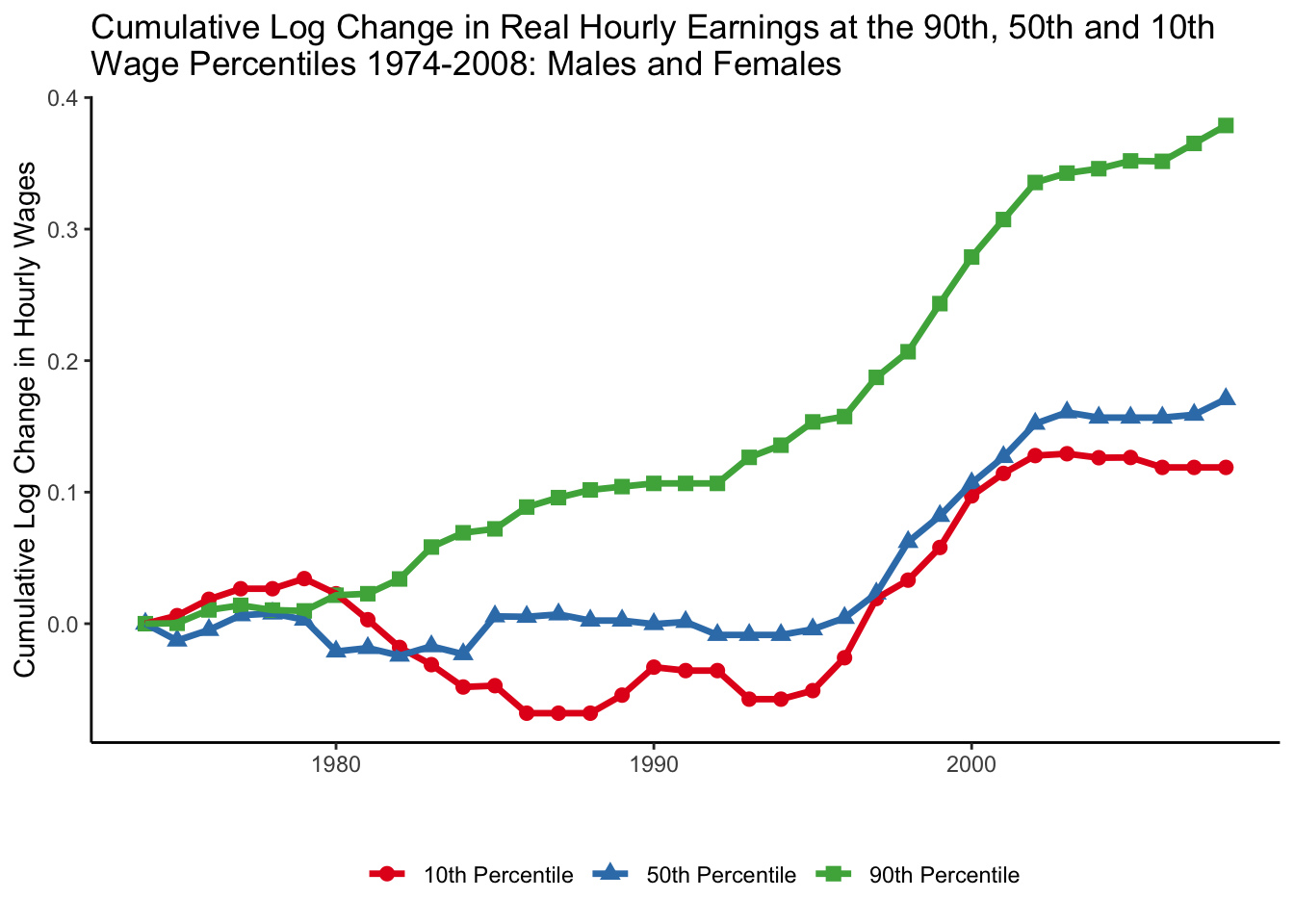

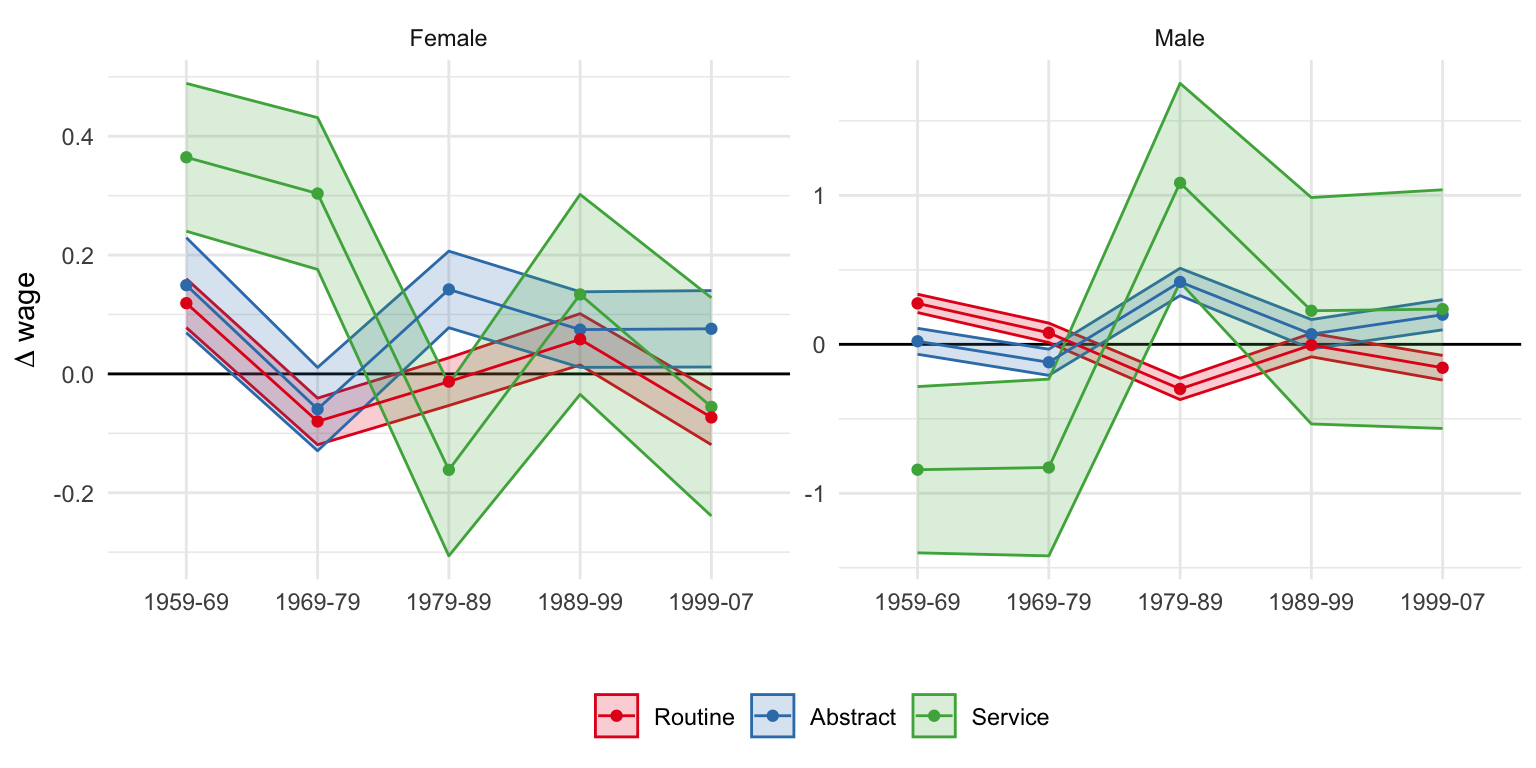

Source: Figures 1 and 2 (Acemoglu and Autor 2011)

Canonical model

Canonical model

Overview

Two types of labour: high- and low-skill

Typically, high edu and low edu (can be relaxed)Skill-biased technological change (SBTC)

New technology disproportionately \(\uparrow\) high-skill labour productivityHigh- and low-skill are imperfectly substitutable

Typically, CES production function with elasticity of substitution \(\sigma\)Competitive labour market

Canonical model

Production function

\[ Y = \left[\left(A_L L\right)^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} + \left(A_H H\right)^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\right]^\frac{\sigma}{\sigma - 1} \]

\(A_L\) and \(A_H\) are factor-augmenting technology terms

\(\sigma \in [0, \infty)\) is the elasticity of substitution

- \(\sigma > 1\) gross substitutes

- \(\sigma < 1\) gross complements

- \(\sigma = 0\) perfect complements (Leontieff production)

- \(\sigma \rightarrow \infty\) perfect substitutes

- \(\sigma = 1\) Cobb-Douglas production

Canonical model

Rationalisation of CES production function

- Single output \(Y\); \(H\) and \(L\) are imperfect substitutes

- Two goods \(Y_H = A_H H\) and \(Y_L = A_L L\); CES utility of consumers \(\left[Y_L^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} + Y_H^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\right]^\frac{\sigma}{\sigma - 1}\)

- Combination of the 1. and 2.

Supply of \(H\) and \(L\) assumed inelastic \(\Rightarrow\) study only firm side

Canonical model

Equilibrium wages

\[ \begin{align} w_L &= A_L^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} \left[A_L^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} + A_H^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\left(\frac{H}{L}\right)^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\right]^\frac{1}{\sigma - 1}\\ w_H &= A_H^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} \left[A_L^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\left(\frac{H}{L}\right)^{-\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}} + A_H^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\right]^\frac{1}{\sigma - 1} \end{align} \]

Comparative statics:

- \(\frac{\partial w_L}{\partial H/L} > 0\) low-skill wage rises with \(\frac{H}{L}\)

- \(\frac{\partial w_H}{\partial H/L} < 0\) high-skill wage falls with \(\frac{H}{L}\)

- \(\frac{\partial w_i}{\partial A_L} > 0\) and \(\frac{\partial w_i}{\partial A_H} > 0, ~\forall i \in \{L, H\}\)

Canonical model

Skill premium

\[ \frac{w_H}{w_L} = \left(\frac{A_H}{A_L}\right)^\frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} \left(\frac{H}{L}\right)^{-\frac{1}{\sigma}} \]

\(\Delta\) relative supply

\[ \frac{\partial \ln \frac{w_H}{w_L}}{\partial \ln \frac{H}{L}} = -\frac{1}{\sigma} < 0 \]

\(\Delta\) technology

\[ \frac{\partial \ln\frac{w_H}{w_L}}{\partial \ln\frac{A_H}{A_L}} = \frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} \lessgtr 0 \]

- Gross substitutes: \(\sigma > 1 \Rightarrow \frac{\partial \ln w_H/ w_L}{\partial \ln A_H / A_L} > 0\)

- Gross complements: \(\sigma < 1 \Rightarrow \frac{\partial \ln w_H/ w_L}{\partial \ln A_H / A_L} < 0\)

- Cobb-Douglas: \(\sigma = 1 \Rightarrow \frac{\partial \ln w_H/ w_L}{\partial \ln A_H / A_L} = 0\)

Tinbergen’s race in the data

Katz and Murphy (1992)

The log-equation of skill premium is extremely attractive for empirical analysis

\[ \ln\frac{w_{H, t}}{w_{L, t}} = \frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} \ln\left(\frac{A_{H, t}}{A_{L, t}}\right) -\frac{1}{\sigma} \ln \left(\frac{H_t}{L_t}\right) \]

Assume a log-linear trend in relative productivities

\[ \ln \left(\frac{A_{H, t}}{A_{L, t}}\right) = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 t \]

and plug it into the log skill premium equation:

\[ \ln\frac{w_{H, t}}{w_{L, t}} = \frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma}\alpha_0 + \frac{\sigma - 1}{\sigma} \alpha_1 t -\frac{1}{\sigma} \ln\left(\frac{H_t}{L_t}\right) \]

Tinbergen’s race in the data

Katz and Murphy (1992)

Estimated the skill premium equation using the US data in 1963-87 \[ \ln \omega_t = \text{cons} + \underset{(0.005)}{0.027} \times t - \underset{(0.128)}{0.612} \times \ln\left(\frac{H_t}{L_t}\right) \]

Implies elasticity of substitution \(\sigma \approx \frac{1}{0.612} =\) 1.63

Agrees with other estimates that place \(\sigma\) between 1.4 and 2 (Acemoglu and Autor 2011)

Tinbergen’s race in the data

Very close fit up to mid-1990s, diverge later

Fit up to 2008 implies \(\sigma \approx\) 2.95

Accounting for divergence:

non-linear time trend in \(\ln\frac{A_H}{A_L}\)

brings \(\sigma\) back to 1.8, but implies \(\frac{A_H}{A_L}\) slowed downdifferentiate labour by age/experience as well

Canonical model

Summary

- Simple link between wage structure and technological change

- Attractive explanation for college/no college wage inequality1

- Average wages \(\uparrow\) (follows from \(\partial w_i / \partial A_H\) and \(\partial w_i/ \partial A_L\))

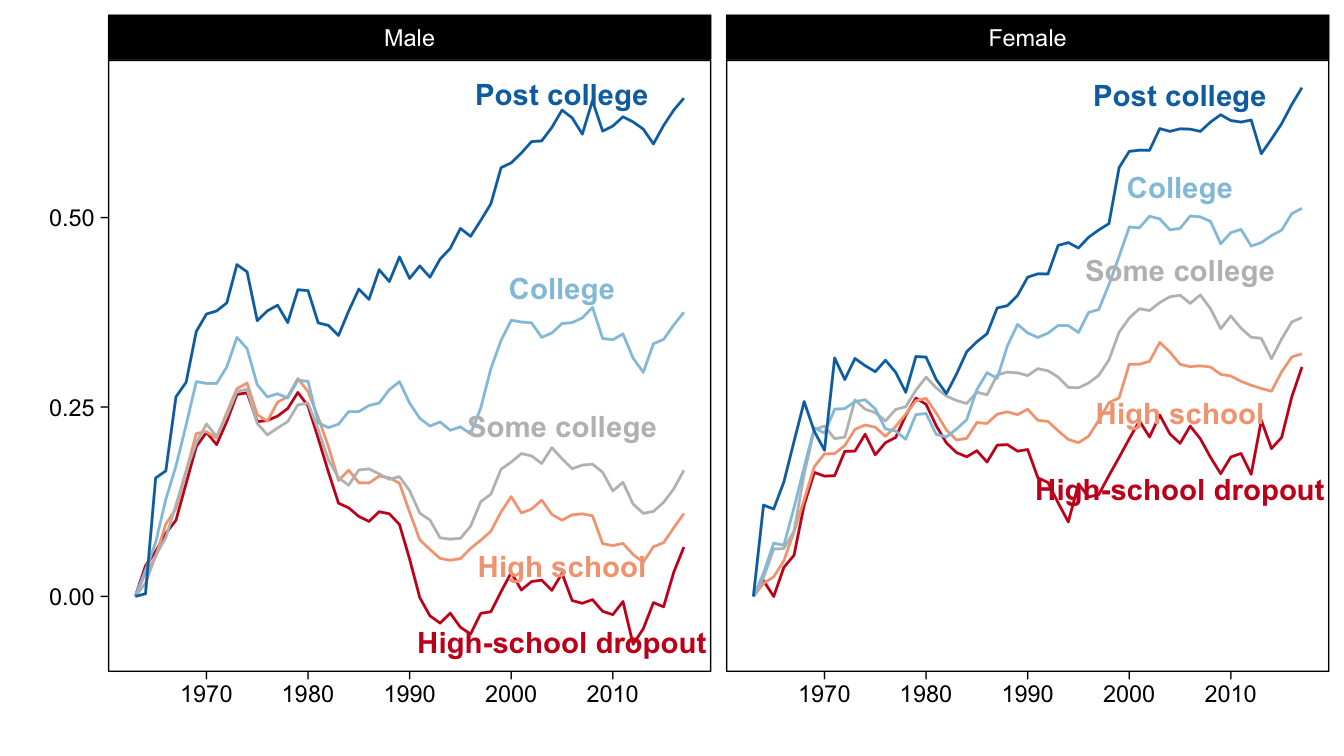

However, the model cannot explain other trends observed in the data:

- Falling \(w_L\)

- Earnings polarization

- Job polarization

Also silent about endogeneous adoption or labour-replacing technology.

Unexplained trend: falling real wages

Source: Figure 1 (Autor 2019)

Unexplained trend: earnings polarization

Source: Figure 8 (Acemoglu and Autor 2011)

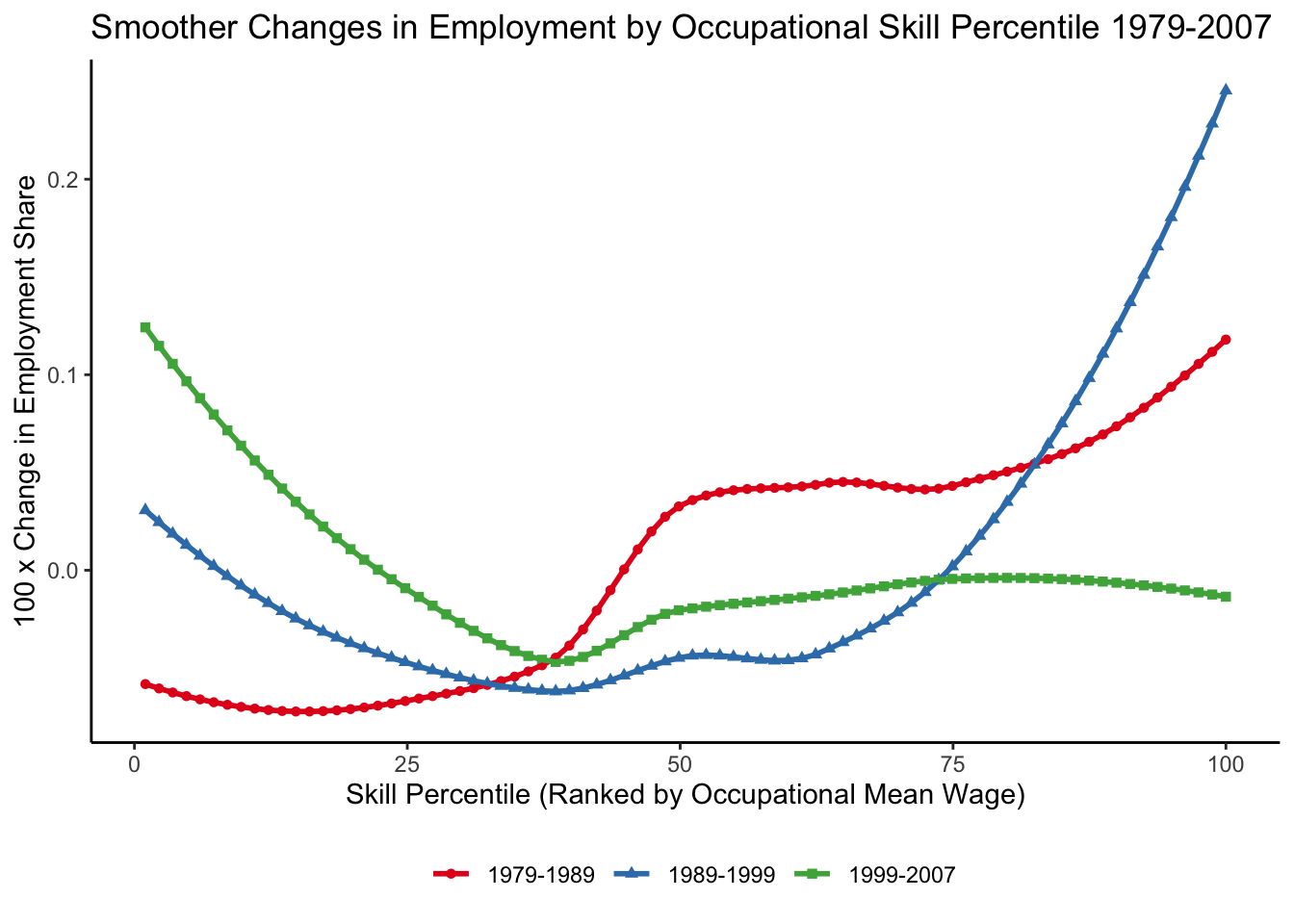

Unexplained trend: job polarization

Source: Figure 10 (Acemoglu and Autor 2011)

Task-based model

Task-based model

Overview

Task is a unit of work activity that produces output

Skill is a worker’s endowment of capabilities for performing tasks

Key features:

- Tasks can be performed by various inputs (skills, machines)

- Comparative advantage over tasks among workers

- Multiple skill groups

- Consistent with canonical model predictions

Task-based model

Production function

Unique final good \(Y\) produced by continuum of tasks \(i \in [0, 1]\)

\[ Y = \exp \left[\int_0^1 \ln y(i) \text{d}i\right] \]

Three types of labour: \(H\), \(M\) and \(L\) supplied inelastically.

\[ y(i) = A_L \alpha_L(i) l(i) + A_M \alpha_M(i) m(i) + A_H \alpha_H(i) h(i) + A_K \alpha_K(i) k(i) \]

\(A_L, A_M, A_H, A_K\) are factor-augmenting technologies

\(\alpha_L(i), \alpha_M(i), \alpha_H(i), \alpha_K(i)\) are task productivity schedules

\(l(i), m(i), h(i), k(i)\) are production inputs allocated to task \(i\)

Task-based model

Comparative advantage assumption

\(\alpha_L(i)/\alpha_M(i)\) and \(\alpha_M(i)/\alpha_H(i)\) are continuously differentiable and strictly decreasing.

Market clearing conditions

\[ \int_0^1 l(i) \text{d}i \leq L \qquad \int_0^1 m(i) \text{d}i \leq M \qquad \int_0^1 h(i) \text{d}i \leq H \]

Task-based model

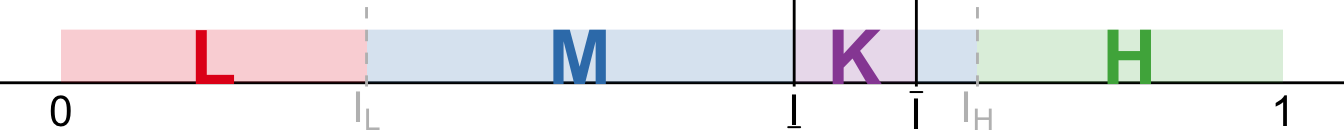

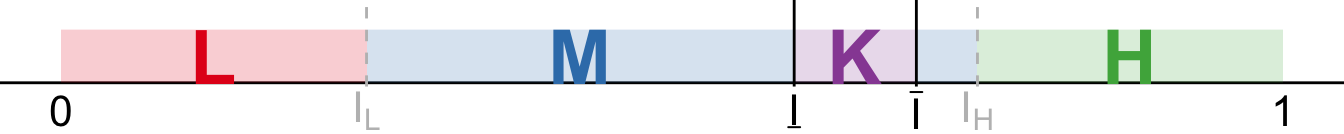

Equilibrium without machines

Lemma 1

Given comparative advantage assumption, there exist \(I_L\) and \(I_H\) such that

Note that boundaries \(I_L\) and \(I_H\) are endogenous

This gives rise to the substitution of skills across tasks

Task-based model

Law of one wage

Output price is normalised to 1 \(\Rightarrow \exp\left[\int_0^1 \ln p(i) \text{d}i\right] = 1\)

All tasks employing a given skill pay corresponding wage

\[\begin{align} w_L &= p(i) A_L \alpha_L(i), \qquad \forall i \in [0, I_L] \\ w_M &= p(i)A_M \alpha_M(i), \qquad \forall i \in (I_L, I_H] \\ w_H &= p(i)A_H \alpha_H(i), \qquad \forall i \in (I_H, 1] \end{align}\]

Task-based model

Skill allocations

Given the law of one wage, we can show that

\[\begin{align*} l(i) &= l\left(i^\prime\right) &\Rightarrow& \quad l(i) = \frac{L}{I_L} \forall i \in [0, I_L] \\ m(i) &= m\left(i^\prime\right) &\Rightarrow& \quad m(i) = \frac{M}{I_H - I_L} \forall i \in (I_L, I_H] \\ h(i) &= h\left(i^\prime\right) &\Rightarrow& \quad h(i) = \frac{H}{1 - I_H} \forall i \in (I_H, 1] \\ \end{align*}\]

Task-based model

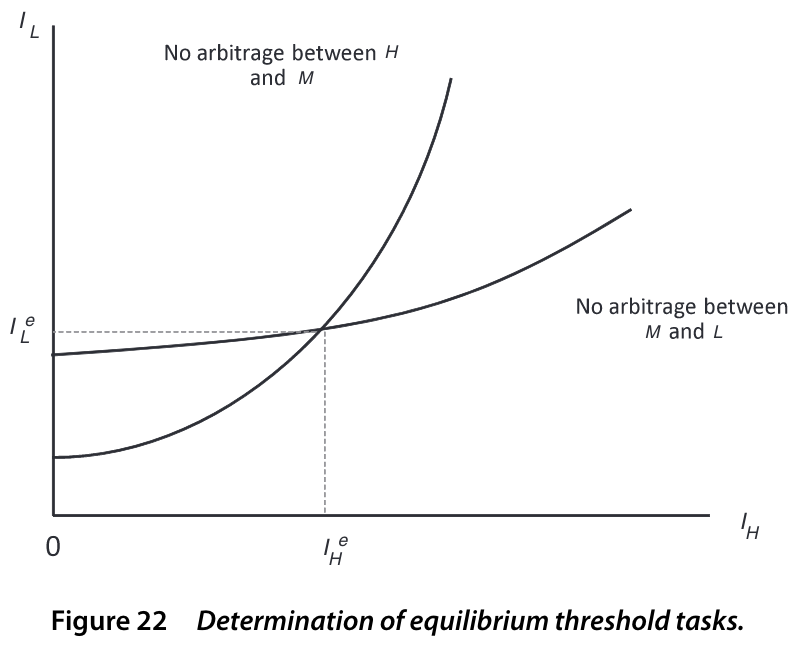

Endogenous thresholds: no arbitrage

Threshold task \(I_H\): equally profitable to produce with either \(H\) or \(M\) skills

\[ \frac{A_M \alpha_M(I_H) M}{I_H - I_L} = \frac{A_H \alpha_H(I_H) H}{1 - I_H} \]

Similarly, for \(I_L\):

\[ \frac{A_L \alpha_L(I_L) L}{I_L} = \frac{A_M \alpha_M(I_L) M}{I_H - I_L} \]

Task-based model

Endogenous thresholds: no arbitrage

Task-based model

Comparative statics: wage elasticities

\[ \begin{matrix} \frac{\text{d} \ln w_H / w_L}{\text{d}\ln A_H} > 0 & \frac{\text{d} \ln w_M / w_L}{\text{d}\ln A_H} < 0 & \frac{\text{d} \ln w_H / w_M}{\text{d}\ln A_H} > 0 \\ \frac{\text{d} \ln w_H / w_L}{\text{d}\ln A_M} \lesseqqgtr 0 & \frac{\text{d} \ln w_M / w_L}{\text{d}\ln A_M} > 0 & \frac{\text{d} \ln w_H / w_M}{\text{d}\ln A_M} < 0 \\ \frac{\text{d} \ln w_H / w_L}{\text{d}\ln A_L} < 0 & \frac{\text{d} \ln w_M / w_L}{\text{d}\ln A_L} < 0 & \frac{\text{d} \ln w_H / w_M}{\text{d}\ln A_L} > 0 \end{matrix} \]

Task-based model

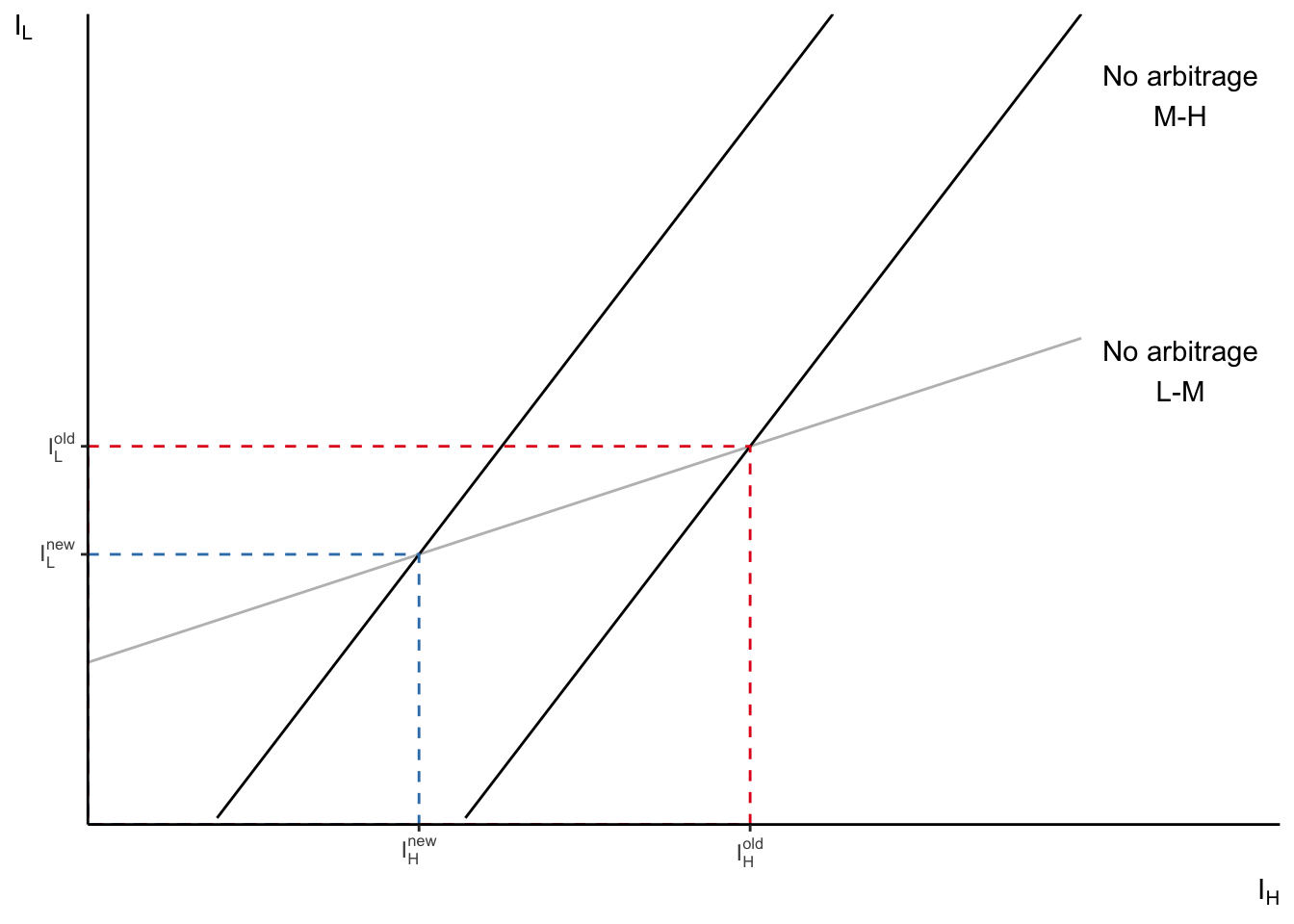

Comparative statics: \(\uparrow A_H\)

Source: Figure 25 (Acemoglu and Autor 2011)

Task-based model

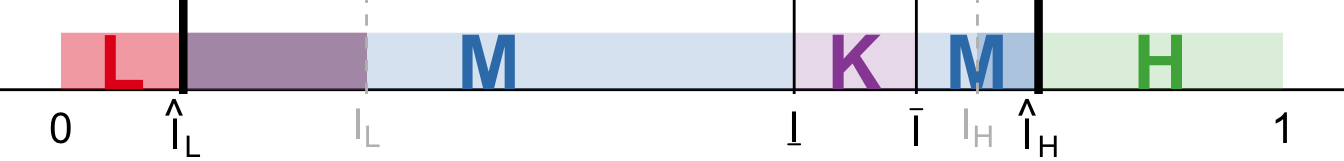

Task replacing technologies

Start from initial equilibrium without machines

Assume in \([\underline{I}, \bar{I}] \subset [I_L, I_H]\) machines outperform \(M\). Otherwise, \(\alpha_K(i) = 0\).

How does it change the equilibrium?

Task-based model

Task replacing technologies

Assume comparative advantage of \(H\) over \(M\) stronger than \(M\) over \(L\)

- \(w_H / w_M\) increases

- \(w_M / w_L\) decreases

- \(w_H / w_L \uparrow \color{#9a2515}{\left(\downarrow\right)}\) if \(\left|\beta^\prime_L(I_L) I_L\right| \stackrel{<}{\color{#9a2515}{>}} \left|\beta^\prime_H(I_H)(1 - I_H)\right|\)

Task-based model

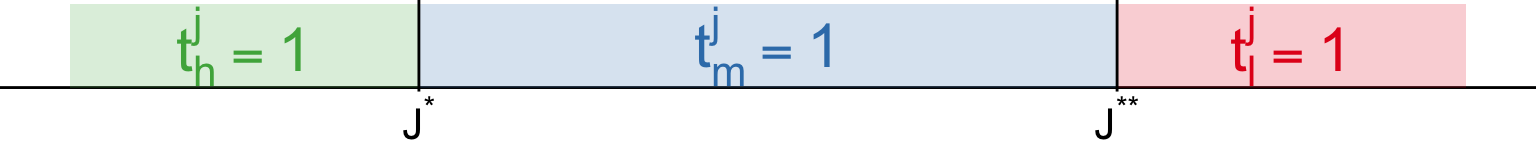

Endogenous supply of skills

Each worker \(j\) is endowed with some amount of each skill \(l^j, m^j, h^j\)

Workers allocate time to each skill given

\[ \begin{align} &t_l^j + t_m^j + t_h^j \leq 1 \\ &w_L t_l^j l^j + w_M t_m^j m^j + w_H t_h^j h^j \end{align} \]

Comparative advantage: \(\frac{h^j}{m^j}\) and \(\frac{m^j}{l^j}\) are decreasing in \(j\)

Then, there exist \(J^\star\left(\frac{w_H}{w_M}\right)\) and \(J^{\star\star}\left(\frac{w_M}{w_L}\right)\)

Task-based model

Illustration in the data

Suppose \(\uparrow A_H \Rightarrow \uparrow \frac{w_H}{w_M}, \downarrow \frac{w_M}{w_L}\).

Use occupational specialization at some \(t = 0\) as comparative advantage.

- \(\gamma_{sejk}^i\) share of 1959 population employed in \(i\) occupations, \(\forall i \in \{H, M, L\}\)

\[ \Delta w_{sejk\tau} = \sum_t \left[\beta_t^H \gamma_{sejk}^H + \beta_t^L \gamma_{sejk}^L\right] 1\{\tau = t\} + \delta_\tau + \phi_e + \lambda_j + \pi_k + e_{sejk\tau} \]

Descriptive regression informed by the model!

Task-based model

Illustration in the data

Source: Table 10 (Acemoglu and Autor 2011)

Task-based model

Summary

- A rich model that can accommodate numerous scenarios

- Outsourcing tasks to lower-cost countries

- Endogenous technological change

- Creation of new tasks

- Useful tool to study effect on inequality and job polarization

Empirical results

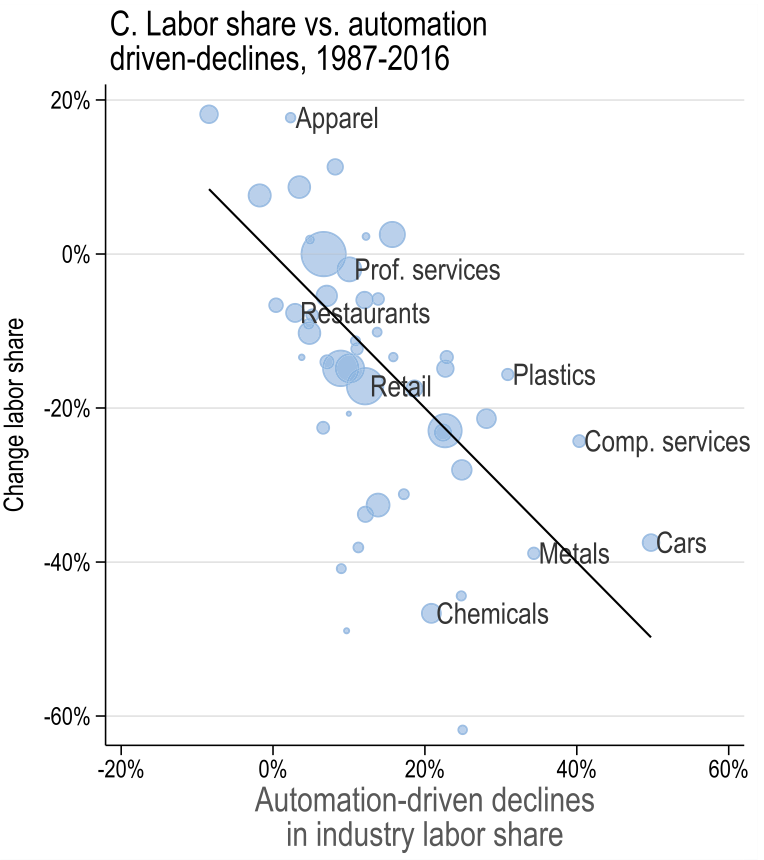

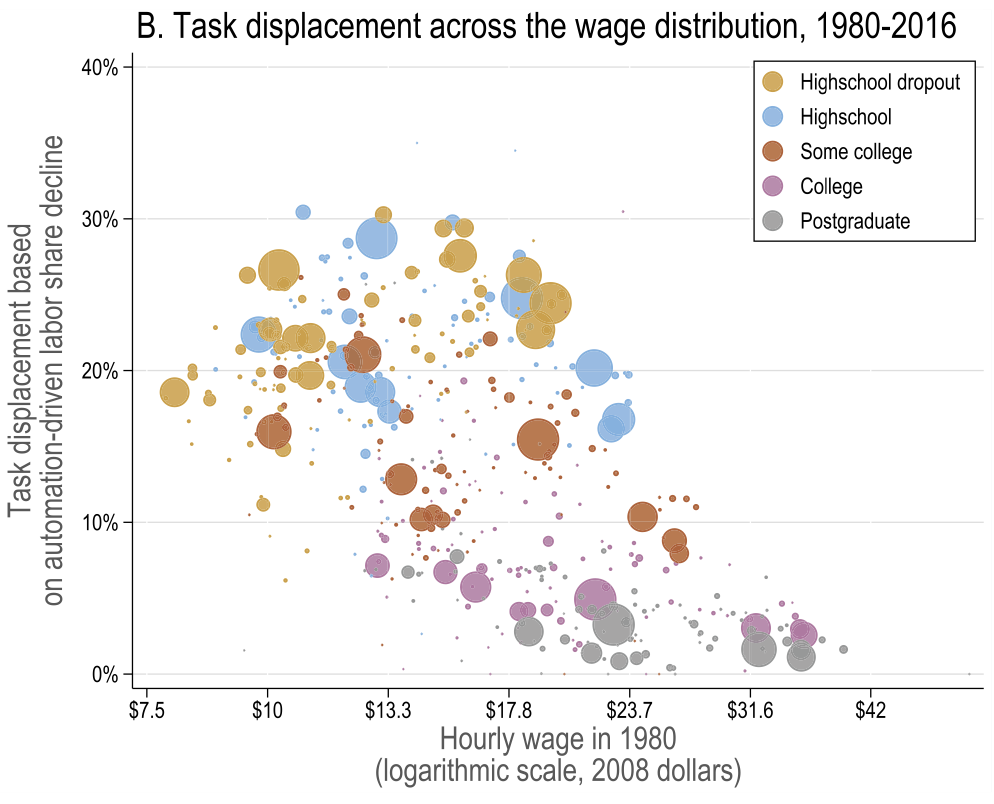

Acemoglu and Restrepo (2022)

Environment

Multi-sector model with imperfect substitution between inputs

\[ \text{Task displacement}_g^\text{direct} = \sum_{i \in \mathcal{I}} \omega_g^i \frac{\omega_{gi}^R}{\omega_i^R} \left(-d \ln s_i^{L, \text{auto}}\right) \]

\(\omega_g^i\) - share of wages earned by worker group \(g\) in industry \(i\)

(exposure to industry \(i\))at \(t=0\)\(\frac{\omega_{gi}^R}{\omega_i^R}\) - specialization of group \(g\) in routine tasks \(R\) within industry \(i\) at \(t=0\)

\(-d \ln s_i^{L, \text{auto}}\) - % decline in industry \(i\)’s labour share due to automation

attribute 100% of the decline to automation

predict given industry adoption of automation technology

Acemoglu and Restrepo (2022)

Task displacement

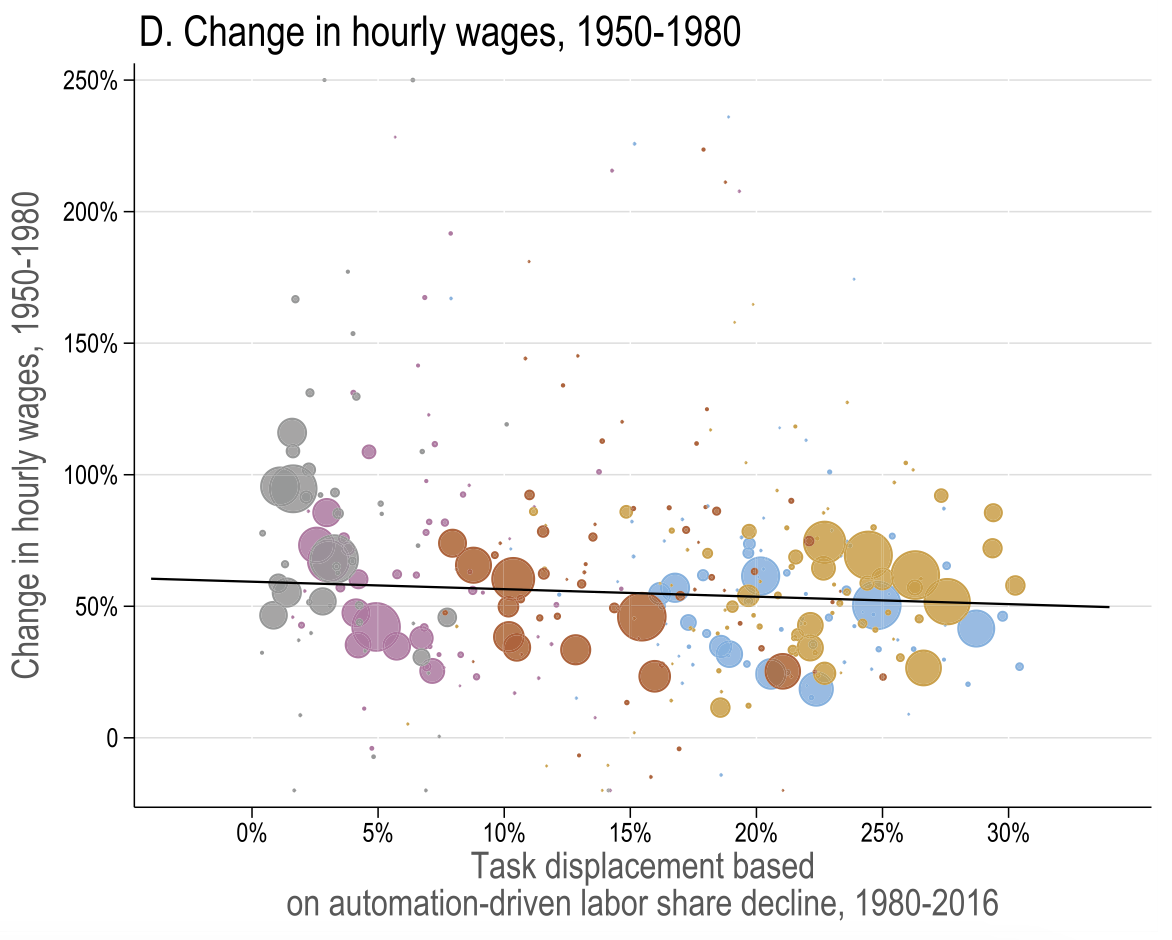

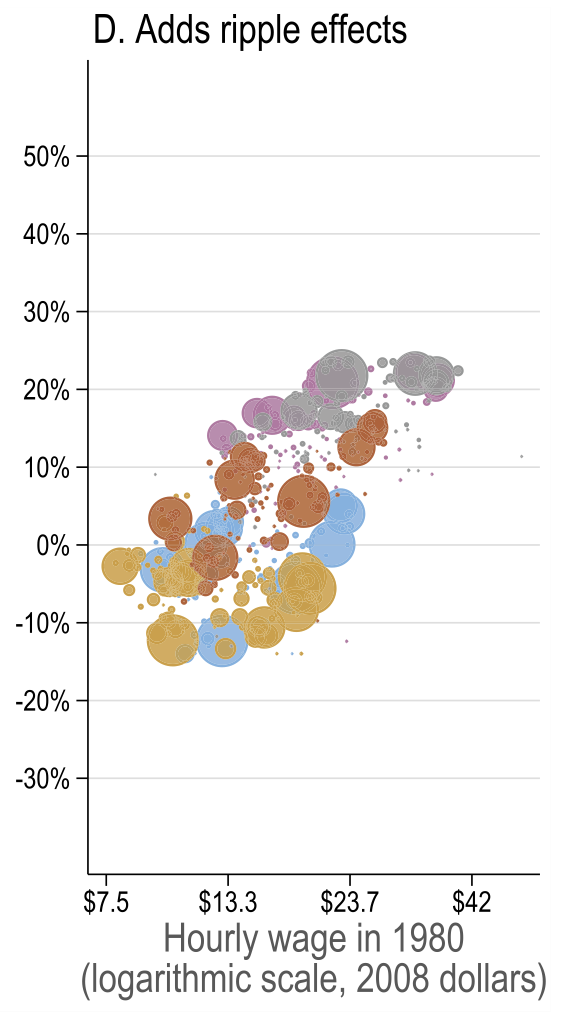

Source: Figure 5

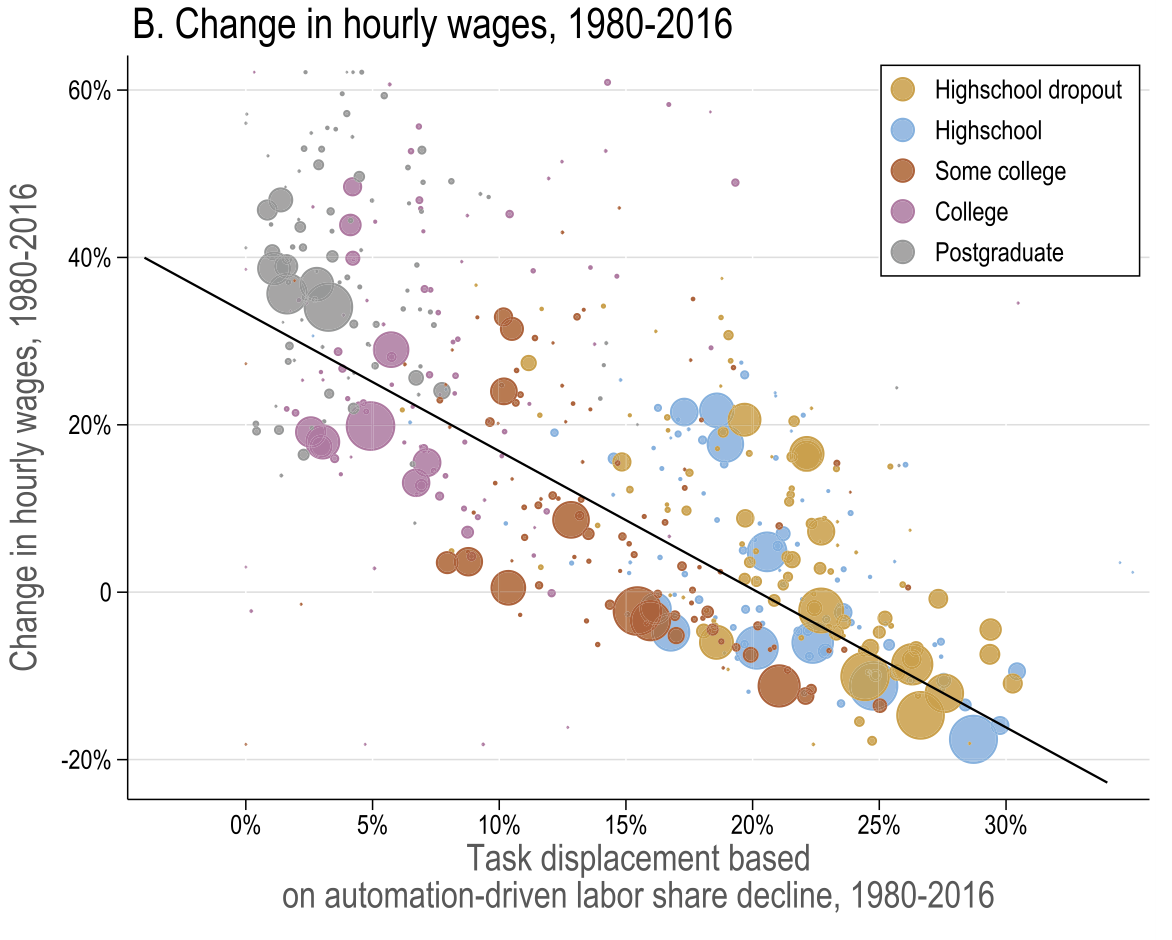

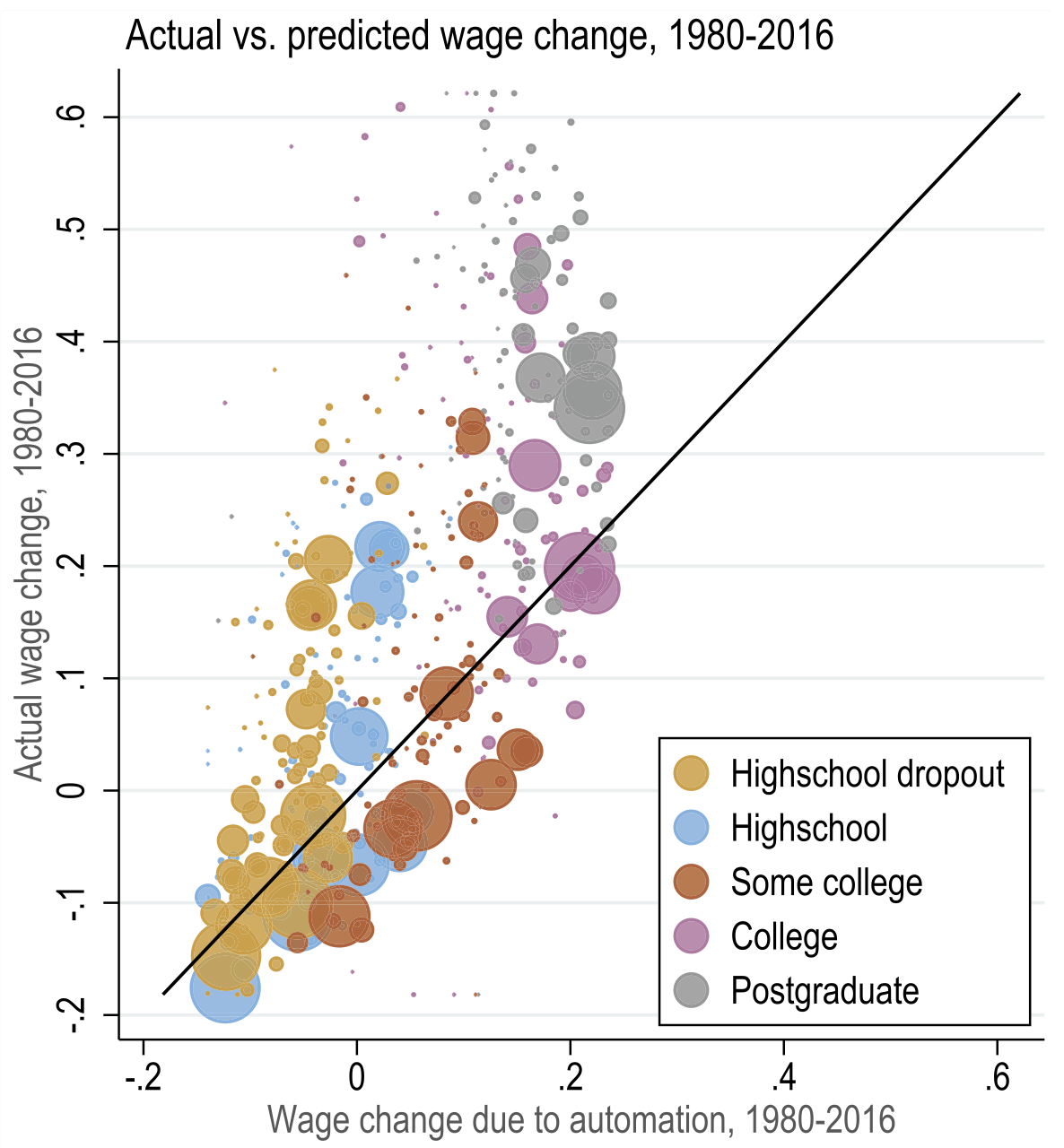

Acemoglu and Restrepo (2022)

Task displacement and changes in real wages

Acemoglu and Restrepo (2022)

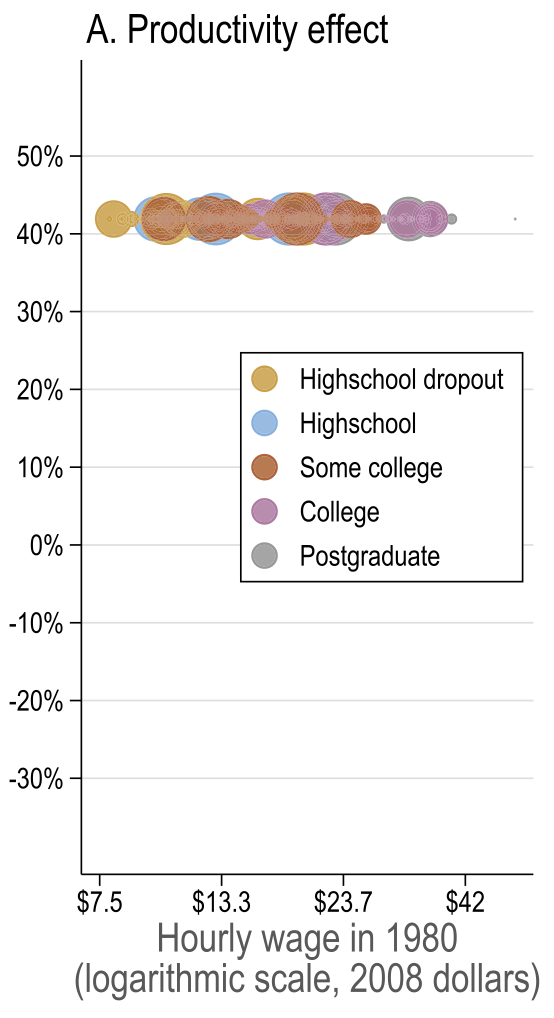

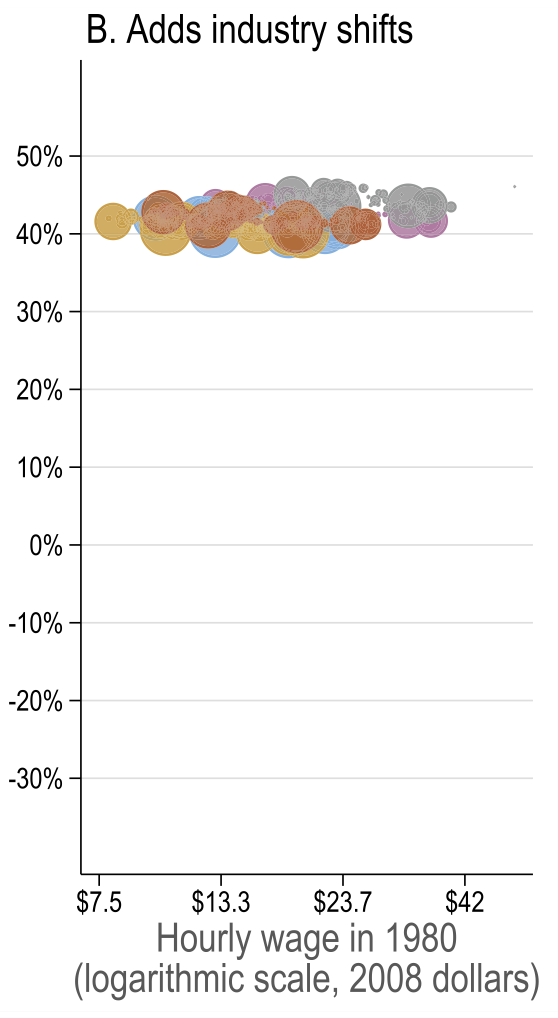

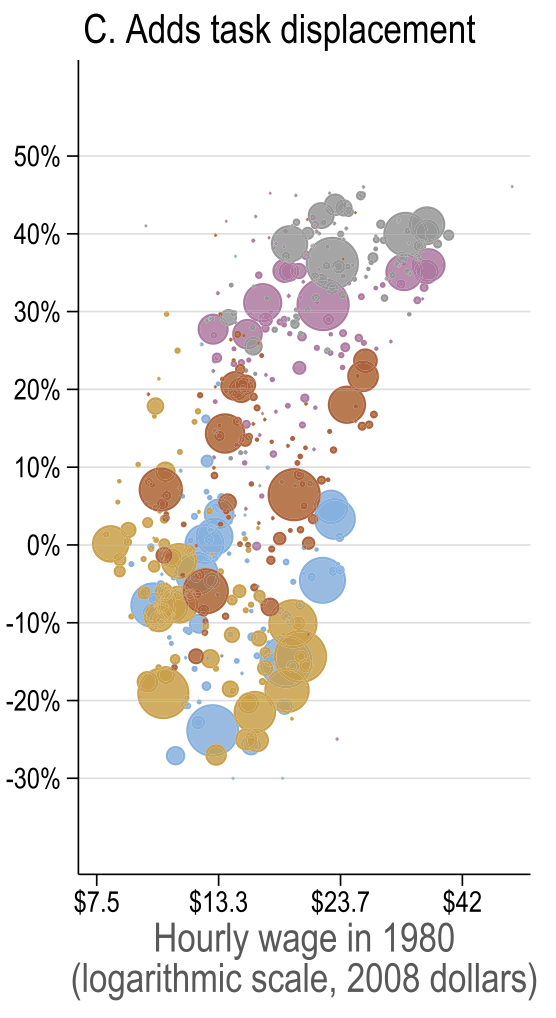

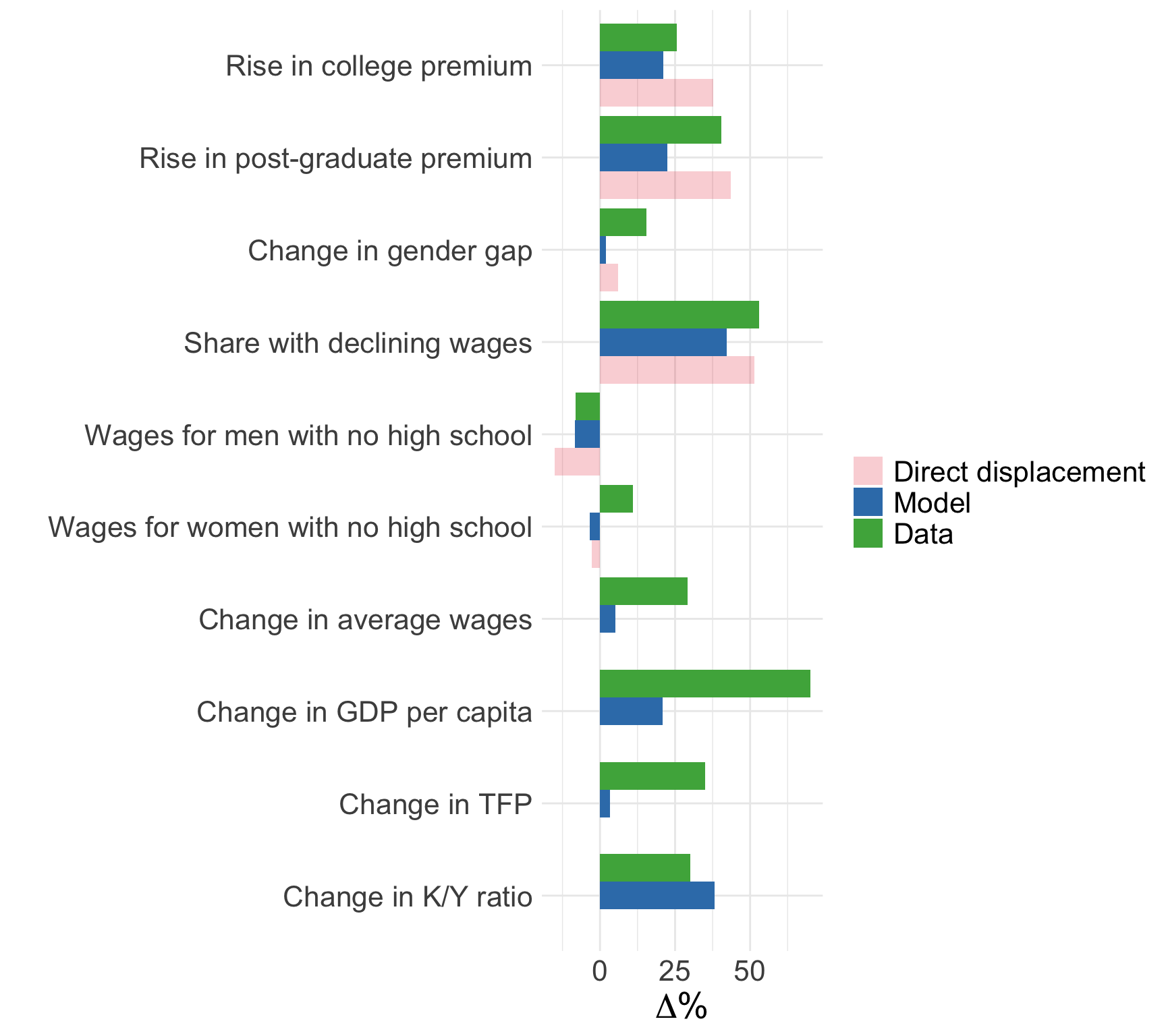

General equilibrium results

Source: Figure 7 (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2022)

Acemoglu and Restrepo (2022)

Model fit

Summary

Two theories linking technological advancements and labour markets

Canonical model (SBTC)

- Simple application of two-factor labour demand theory

- Empirically attractive characterization of between-group inequality

- Fails to account for within-group inequality, polarization, and displacement

Task-based model (automation)

- Rich model linking skills to tasks to output

- Explains large share of changes in the wage structure since 1980s

Next lecture: Labour market discrimination on 22 Sep

Appendix: derivation of wage equations

The firm problem is to choose entire schedules \(\left(l(i), m(i), h(i)\right)_{i=0}^1\) to

\[ \max_{\left(l(i), m(i), h(i)\right)_{i=0}^1} PY - w_L L - w_M M - w_H H \]

We normalised \(P=1\). Consider FOC wrt \(l(i)\):

\[ \frac{Y}{y(i)} A_L \alpha_L(i) = w_L, \qquad \forall i \in [0, I_L] \]

In equilibrium, all \(L\)-type workers must be paid same amount \(\Rightarrow\)

\[ p(i)A_L\alpha_L(i) = w_L, \qquad \forall i \in [0, I_L] \]

Similar argument for \(w_M\) and \(w_H\).

Appendix: derivation of skill allocations

Given the law of one price (wage) we can also write that

\[ p(i)\alpha_L(i)l(i) = p\left(i^\prime\right) \alpha_L\left(i^\prime\right) l\left(i^\prime\right), \qquad \forall i, i^\prime \in [0, I_L] \]

Given the Appendix: derivation of wage equations, it implies that

\[ l(i) =l\left(i^\prime\right) = l, \qquad \forall i, i^\prime \in[0, I_L] \]

Plug it into the market clearing condition for \(L\)

\[ L = \int_0^{I_L} l(i) \text{d}i = l \cdot I_L \quad \Longrightarrow \quad l(i) = l = \frac{L}{I_L}, \forall i \in [0, I_L] \]

Similar argument for \(m(i) = \frac{M}{I_H - I_L}\) and \(h(i) = \frac{H}{1 - I_H}\).