5. Wage setting

KAT.TAL.322 Advanced Course in Labour Economics

September 8, 2025

- Why do wages differ between workers?

- Compensating differentials

- Bargaining power of firms and workers

- Imperfect information about productivities and jobs

- Relative contributions of different sources to overall wage inequality

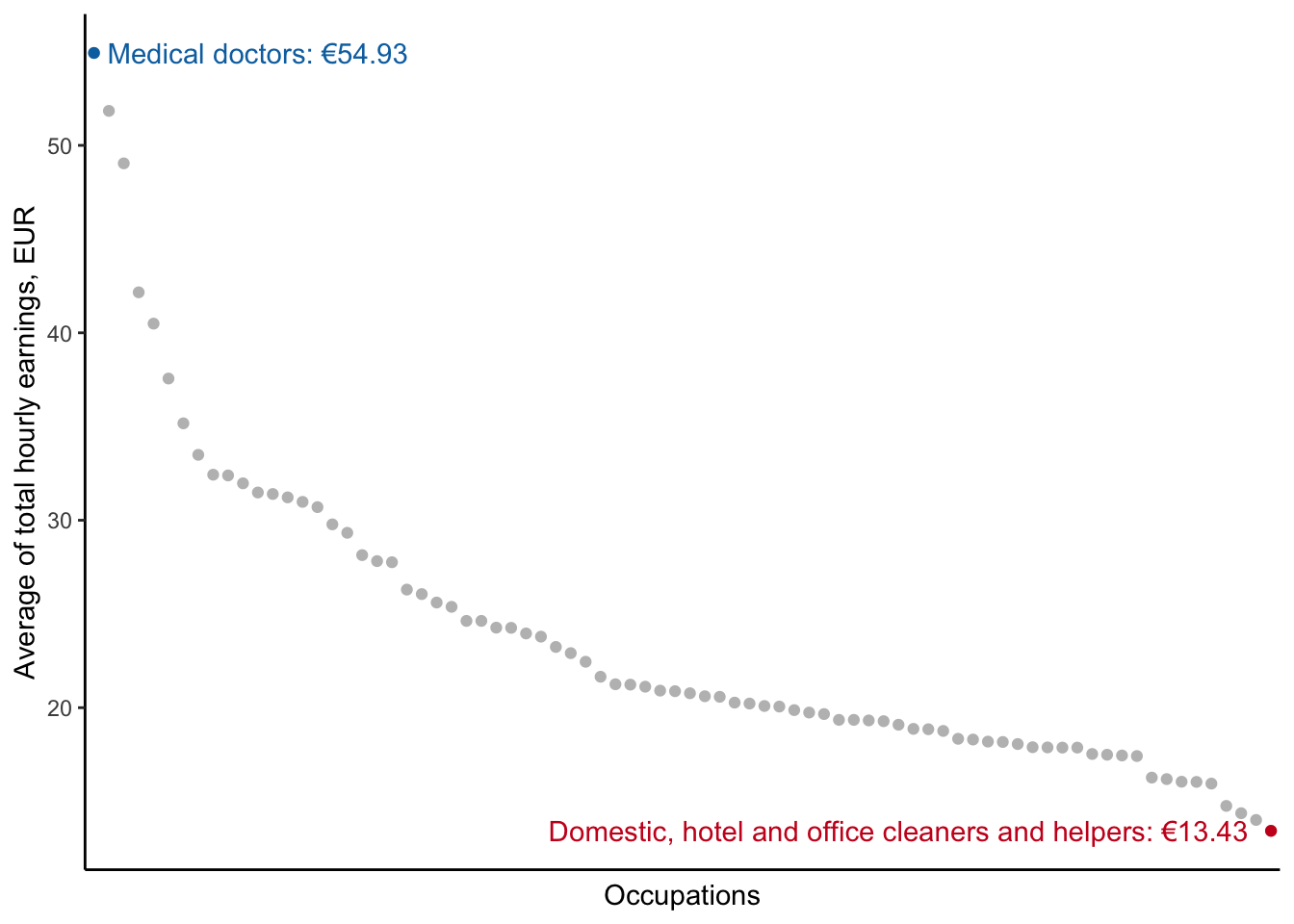

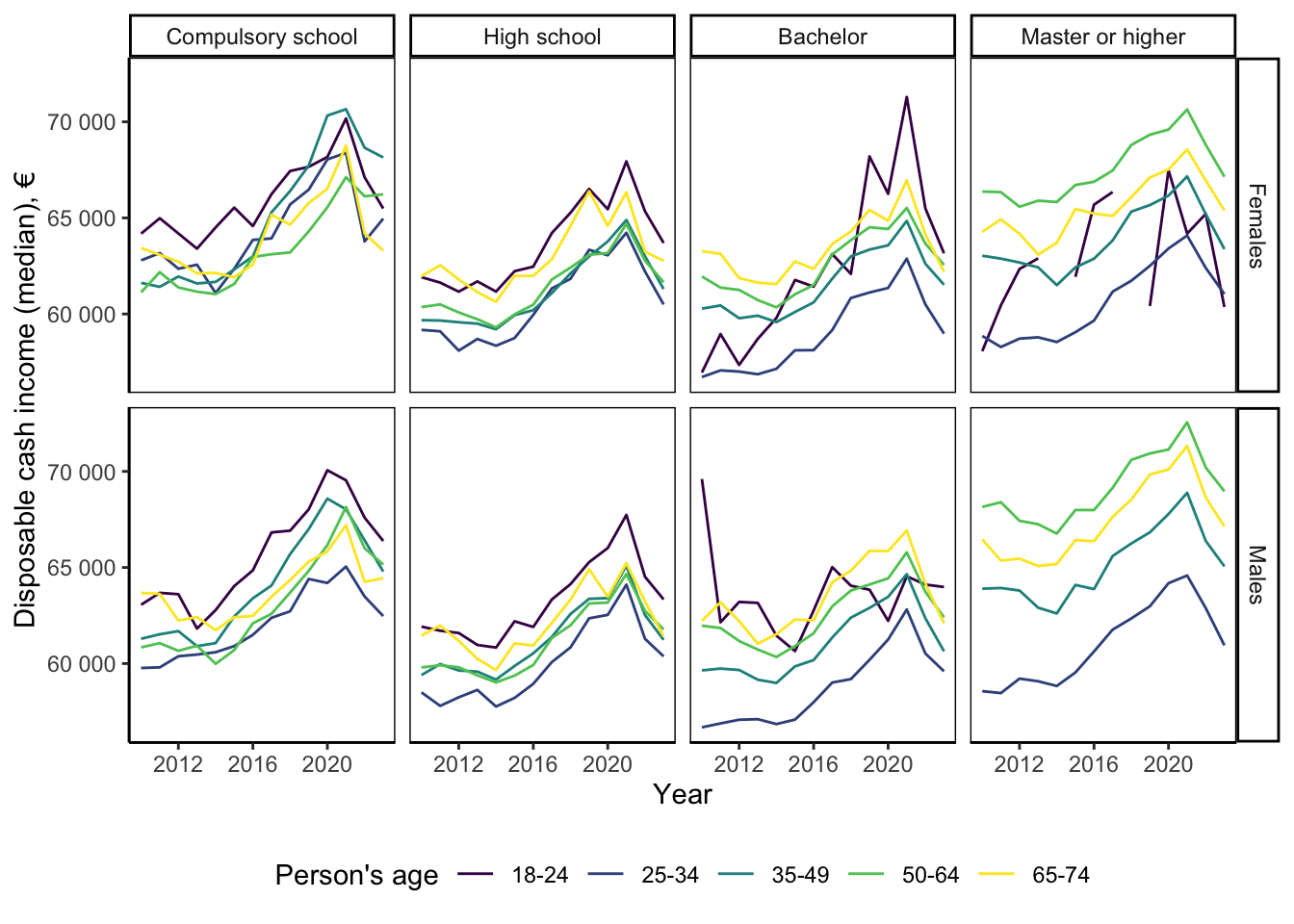

Stylised facts

Wage dispersion

Source: Statistics Finland

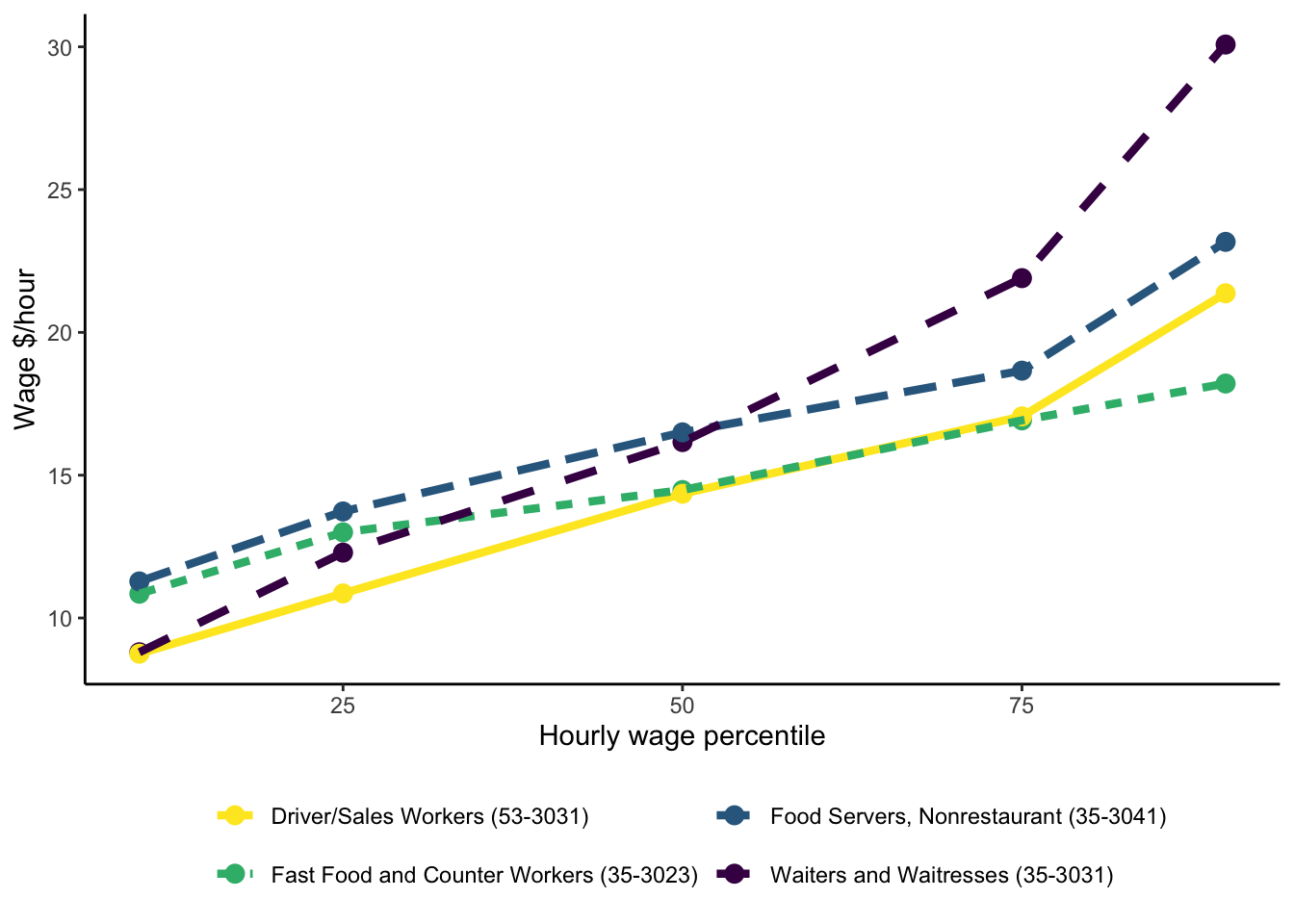

Variation by occupation

Market imperfections?

Source: Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (US)

Perfect competition

Jobs of equal difficulty

Production function \(F(L): F_L(L) = y\)

Workers supply \(h=1\) unit of labour and receive wage \(w\) if hired

Linear worker utility \(U(R, e, \theta) = R - e\theta\)

- \(R = w\) if employed; \(R=0\) otherwise

- \(e\) difficulty of jobs, \(e=1\) is constant

- \(\theta \geq 0\) heterogeneous disutility (\(G_\theta(\cdot)\) CDF)

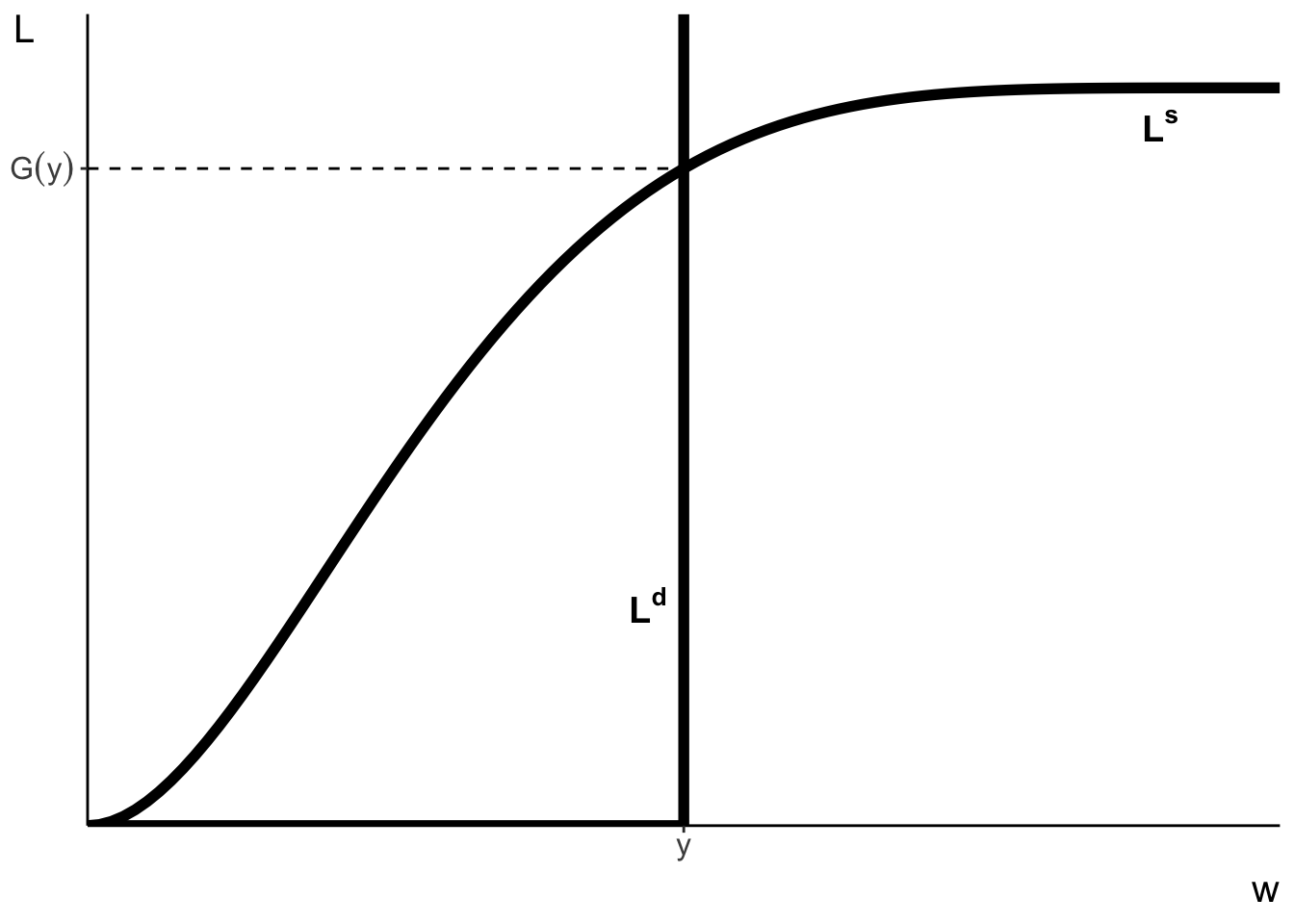

Equilibrium

\[ L^d = \begin{cases}+\infty & \text{if } w < y \\ [0, +\infty) & \text{if } w = y \\ 0 & \text{if } w > y\end{cases} \]

\[ L^s = G(w) \]

Jobs of equal difficulty

Jobs of varying difficulty

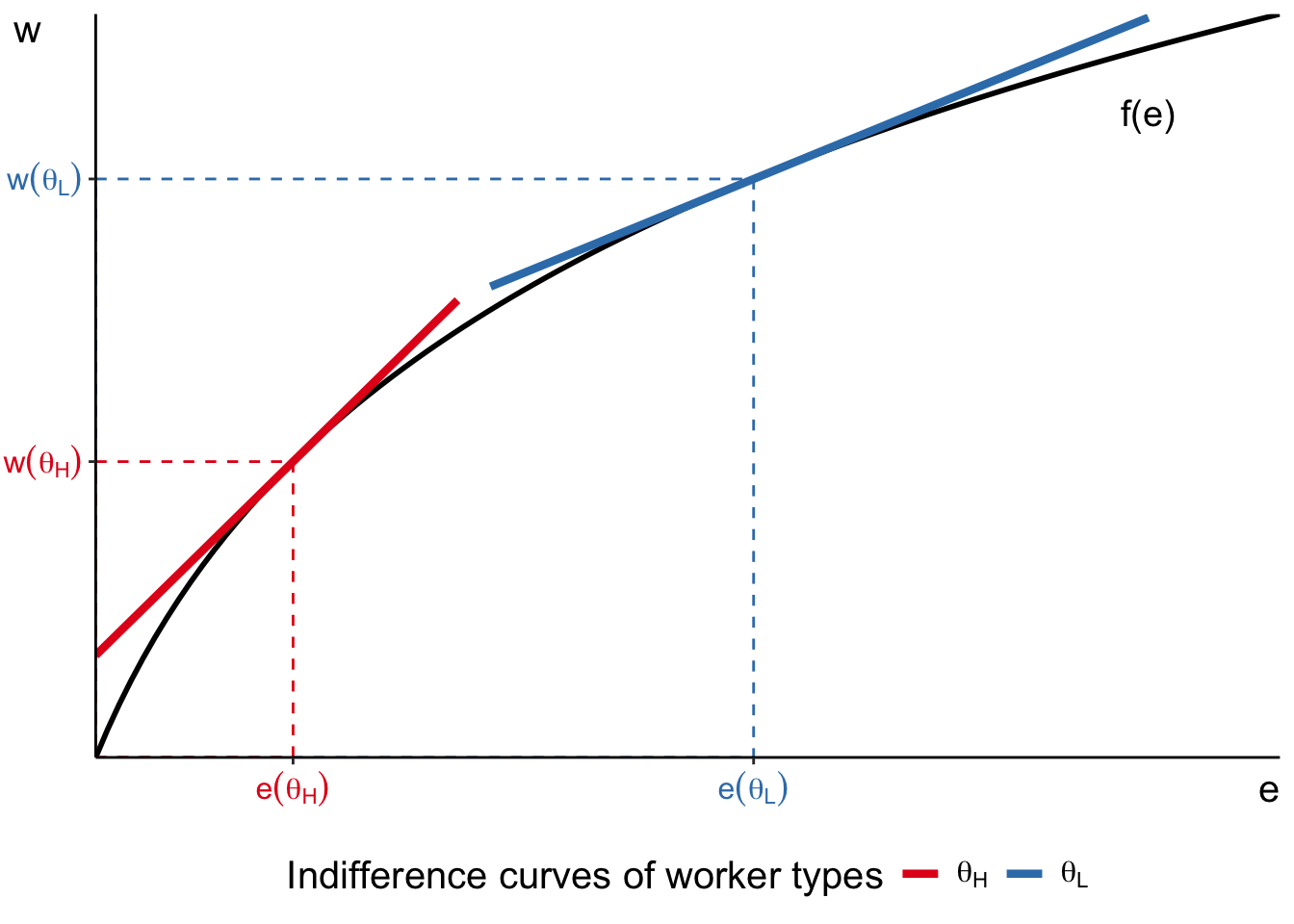

Continuum of jobs with varying difficulty \(e > 0\)

Productivity \(y = f(e)\) such that \(f^\prime(e) > 0, f^{\prime\prime}(e) < 0, f(0) = 0\)

\(e\) also corresponds to effort worker puts in if employed

Compensating wage differentials: \(w^\prime(e) > 0\)

\[ L^d = \begin{cases}+\infty & \text{if } w(e) < f(e) \\ [0, +\infty) & \text{if } w(e) = f(e) \\ 0 & \text{if } w(e) > f(e)\end{cases} \]

\[ L^s = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } f^\prime(e) = \theta \cap f(e) - e\theta \geq 0 \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \]

Jobs of varying difficulty

Workplace safety regulation

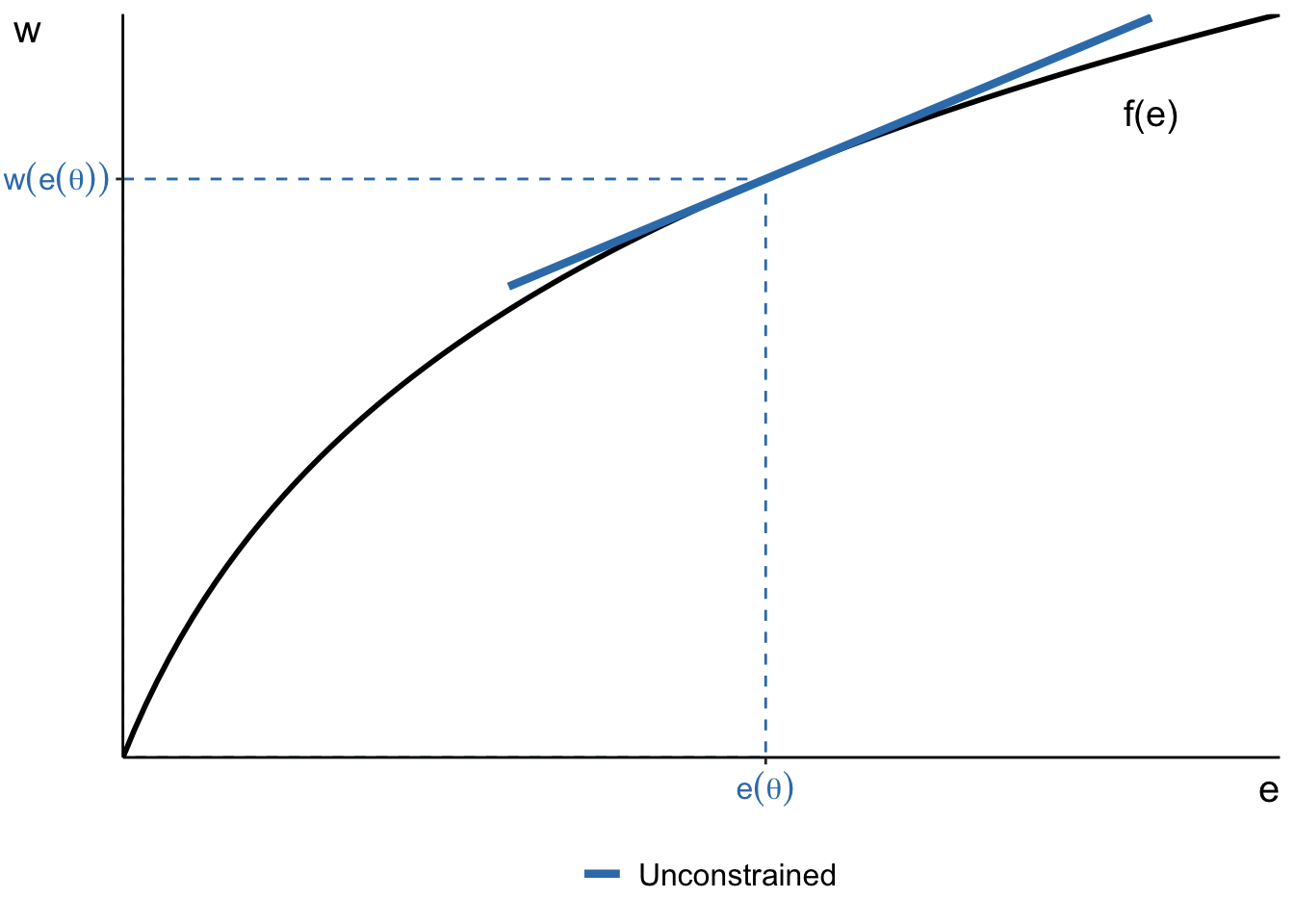

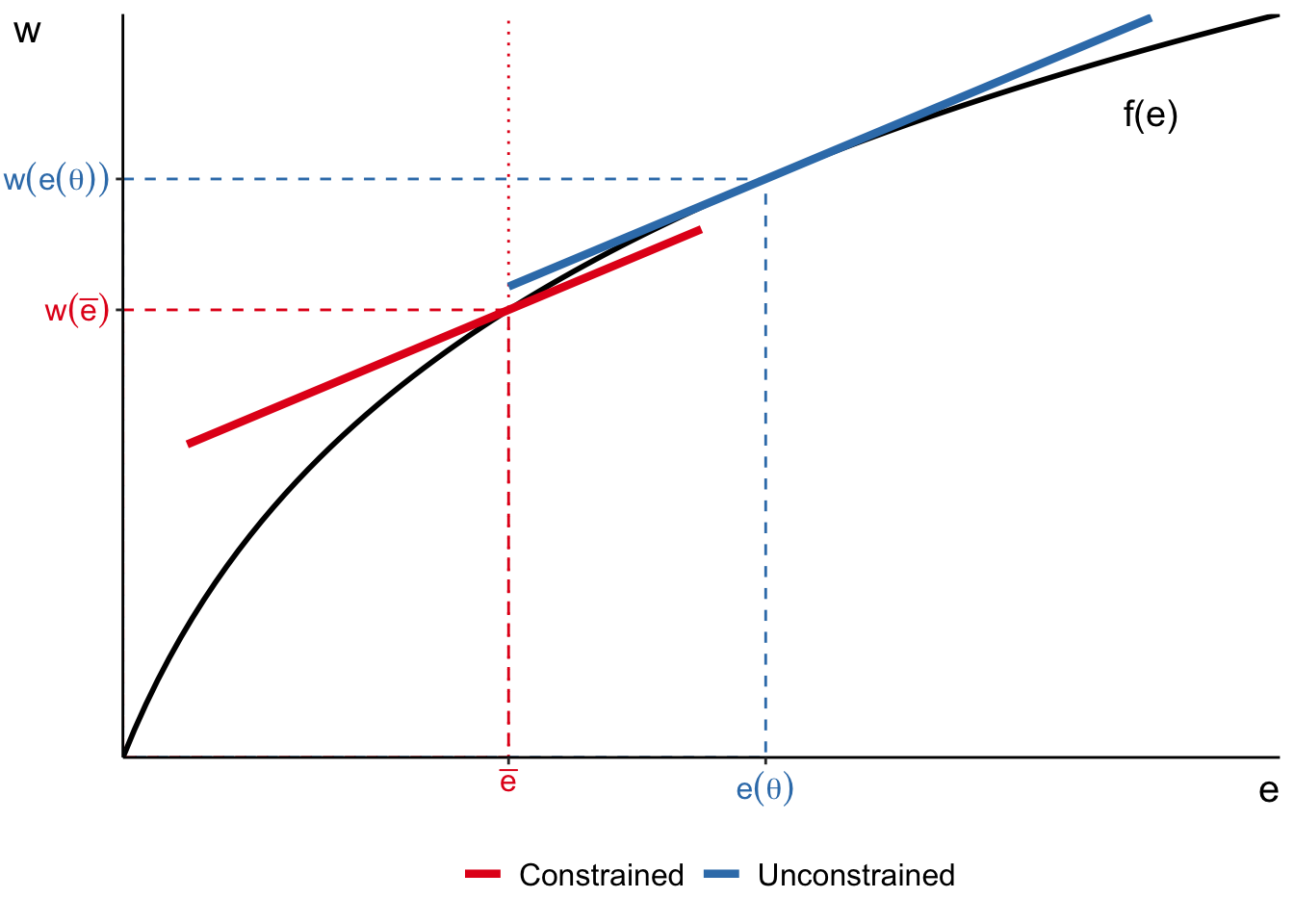

At baseline worker of type \(\theta\) chooses optimal effort \(e(\theta)\) and earns \(w(e(\theta))\)

Workplace safety regulation

Limit on job difficulty \(\bar{e}\) forces worker type \(\theta\) on a lower indifference curve

Perfect competition: summary

- Even under perfect competition, wages and labour supply decisions of workers depend on

- abilities of workers: more productive workers earn higher wages

- characteristics of jobs: more difficult jobs offer higher wages

- Efficient allocation of resources

- part of the population may choose not to work because jobs are not attractive enough

Imperfect competition

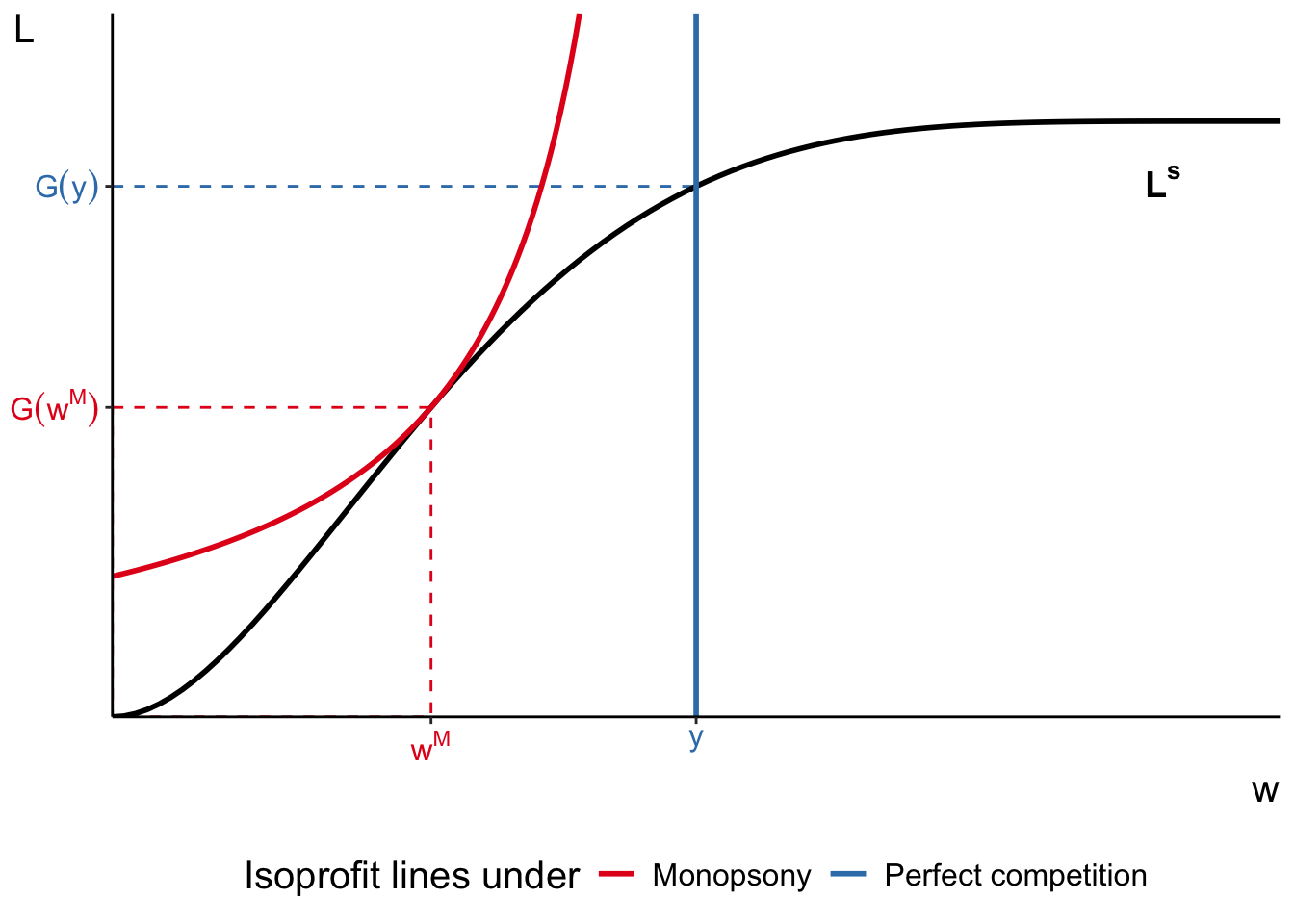

Barriers to entry: monopsonistic employer

Start from baseline model

- Continuum of workers \(\theta\) with utility \(U(R, e, \theta) = R - e\theta, ~ e = 1\)

- Monopsonistic employer \(\max_w \pi(w) \equiv \max_w L^s(w) (y - w)\)

Equilibrium wage \(w^M = y\frac{\eta^L_w(w^M)}{1 + \eta^L_w(w^M)}\) where \(\eta^L_w(w^M) = \frac{w^M}{L^s(w^M)}\frac{\text{d}L^s(w^M)}{\text{d}w}\)

Equilibrium employment \(L^s(w^M) = G(w^M)\)

Barriers to entry: monopsonistic employer

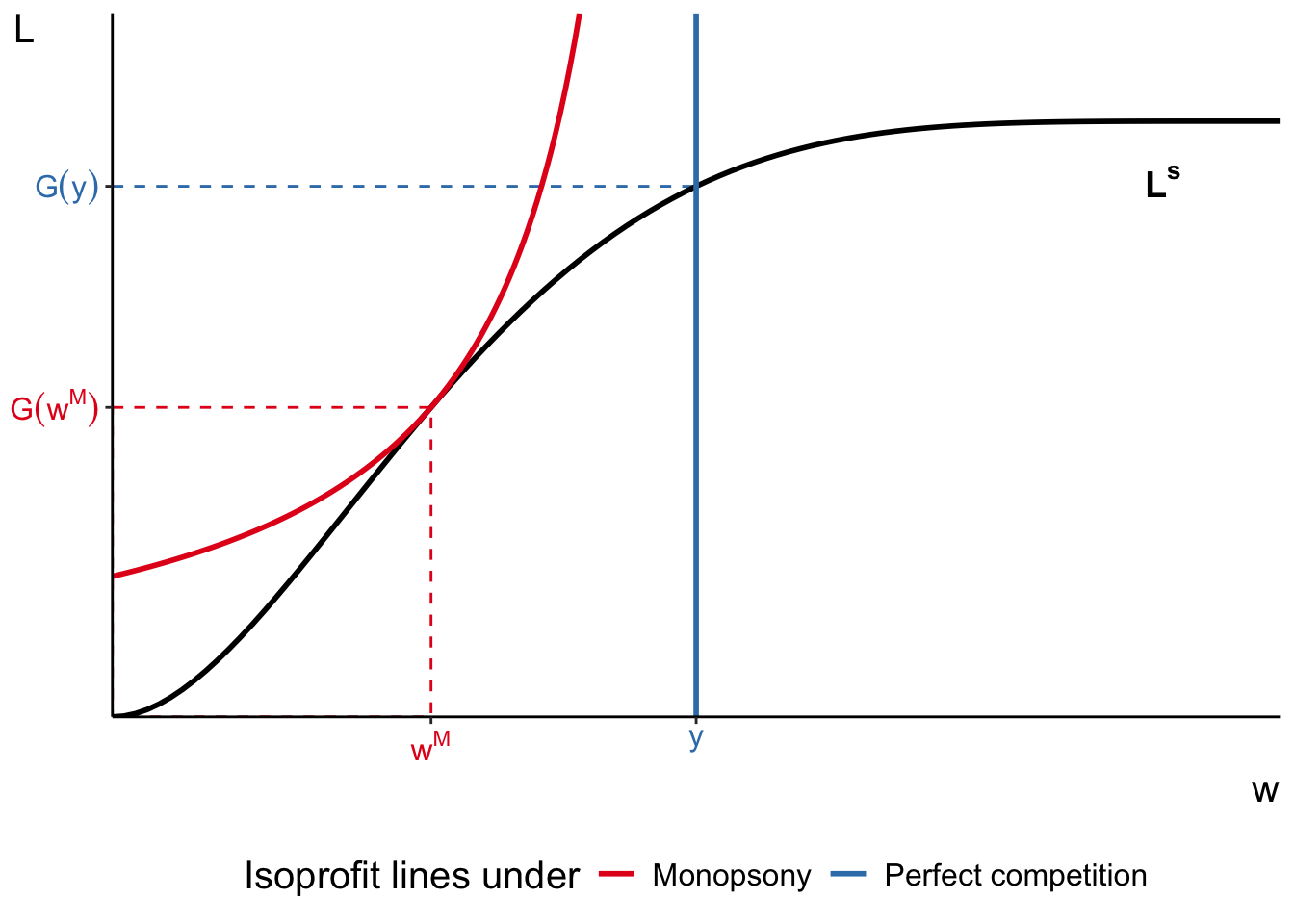

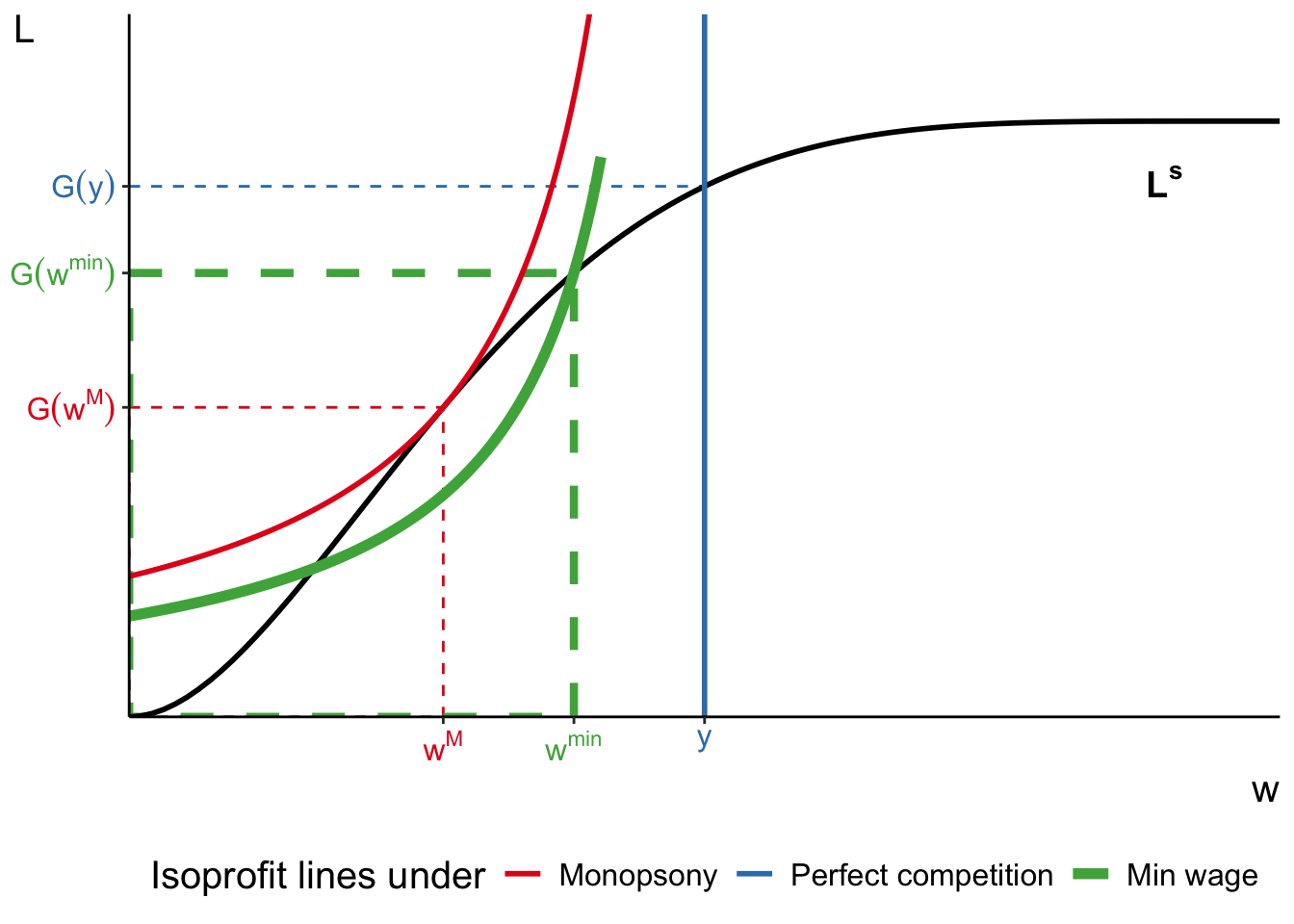

Monopsonistic employer and minimum wage

What happens if government mandates min wage \(w^M < w^\text{min} < y\)?

Monopsonistic employer and minimum wage

Equilibrium employment and wages both rise!

Imperfect information and adverse selection

- Workers are now described by their ability \(h > 0\) with CDF \(G(\cdot)\)

- produce \(h\) units of good

- enjoy leisure utility \(d(h)\) such that \(d^\prime(h) > 0\) and \(d(h) < h\)

- Workers enjoy utility \(U(R, d) = \begin{cases} w(h) & \text{if hired}\\ d(h) & \text{otherwise}\end{cases}\)

- Firms now offer identical jobs \(e = 1\) and \(\max_L \mathbb{E}\left[(h - w(h))L\right]\)

- Firms do not observe true \(h\) of workers (only see the distribution \(G(\cdot)\))

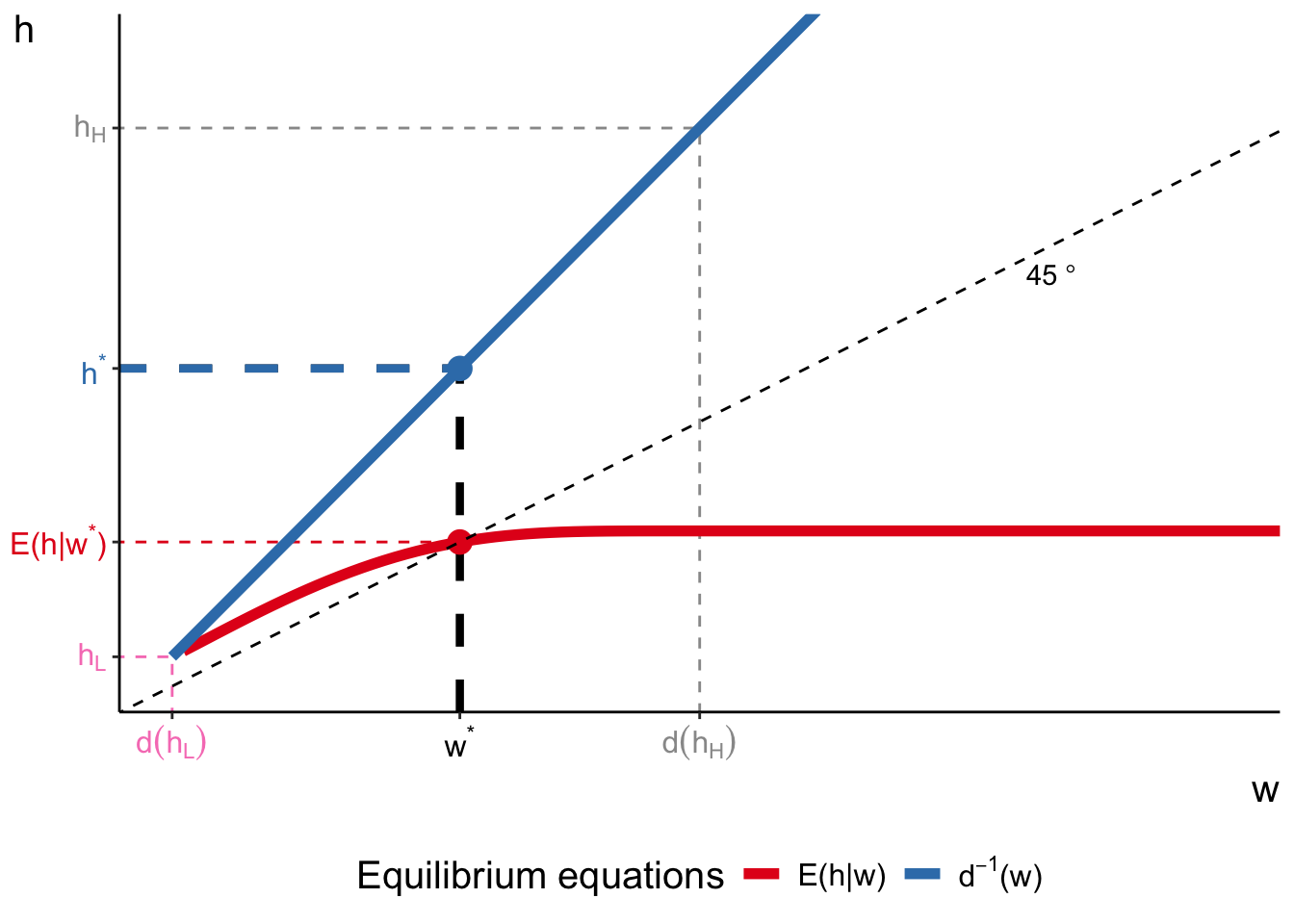

Imperfect information and adverse selection

Equilibrium is described by a pair \((w^\star, h^\star)\) such that

- all workers with \(h < h^\star = d^{-1}(w^\star)\) decide to work

- firms hire all workers ready to work at \(w^\star = \mathbb{E}\left(h | w^\star\right)\)

We can graphically illustrate the equilibrium by plotting \(d^{-1}(w)\) and \(\mathbb{E}\left(h | w\right)\) on the next slide

Imperfect information and adverse selection

Imperfect competition: summary

Wages no longer reflect productivity differences alone

- monopsonistic employer: equilibrium wages and employment \(\downarrow\)

- innovation and mobility costs (Cahuc 2004, ch 5.2)

- trade unions (Cahuc 2004, ch 7)

- Workers and firms may have incomplete information about each other

- In the example, where firms do not know true worker productivities

- \(w^\star\) may be too high for some workers and too low for others

- adverse selection: most productive workers stay unemployed

- Last lecture, workers have imperfect information about jobs

- with on-the-job search and endogenous wages, \(w > y\) for senior workers

Empirical evidence

Estimates of compensating differentials

Regression of wage \(w\) on job difficulty \(e\)

\[ \ln w_i = \mathbf{x}_i \boldsymbol{\beta} + \mathbf{e}_{J(i)} \boldsymbol{\alpha} + \varepsilon \]

- \(\mathbf{x}_i\) - observed worker characteristics

- \(\mathbf{e}_{J(i)}\) - observed job characteristics of worker \(i\)

Early estimates biased by

- unobserved heterogeneity in productivity

- unobserved heterogeneity in preferences

Estimates of compensating differentials

Unobserved heterogeneity in productivity

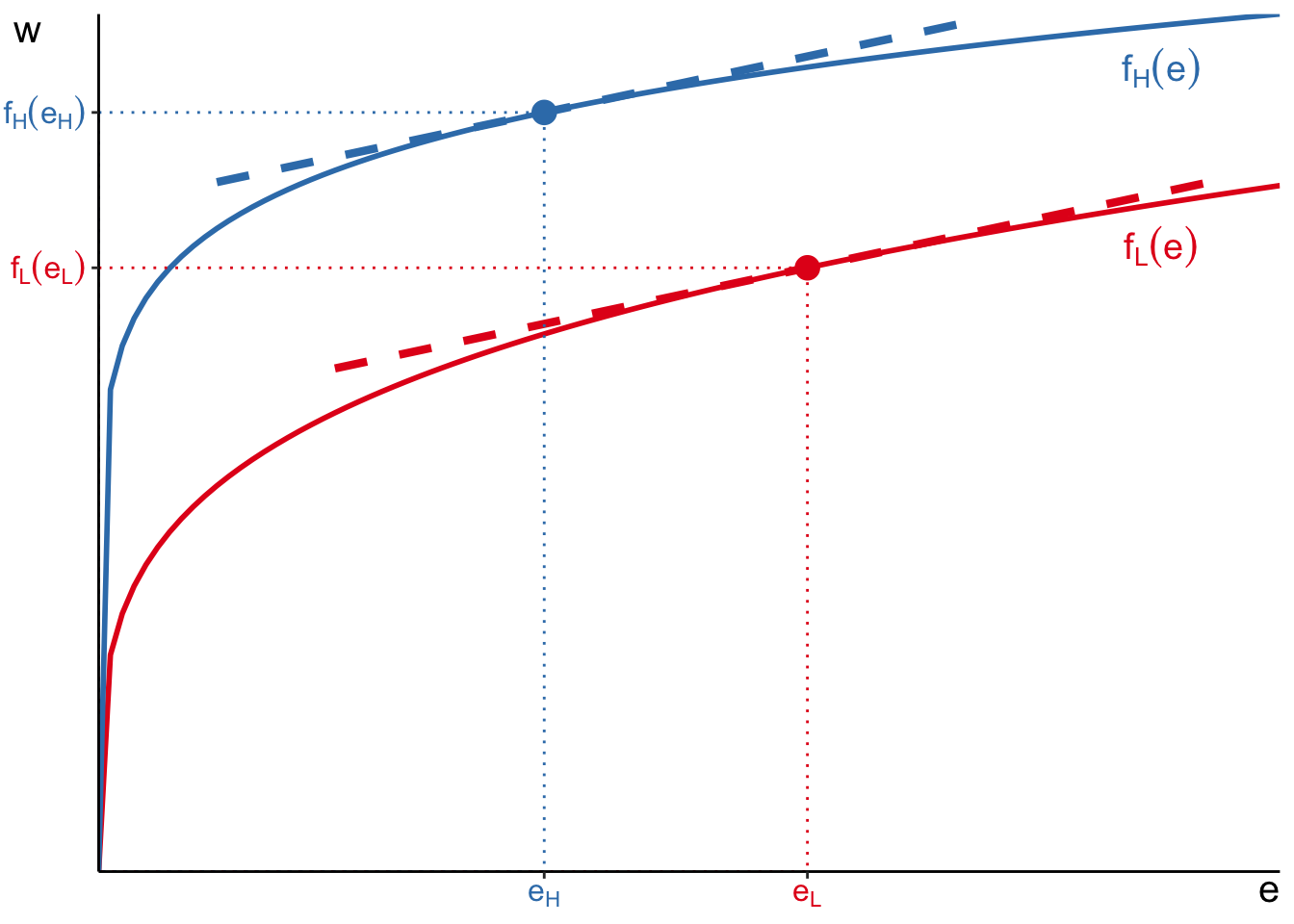

Consider again model with varying \(e\) and two workers with \(f_H(e), f_L(e)\)

Estimates of compensating differentials

Hwang, Reed, and Hubbard (1992)

| Thaler and Rosen (1976) | Hwang et al. (1992) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 3.890 | 4.500 |

| (0.800) | ||

| Age \(^2\) | -0.048 | -0.096 |

| (0.009) | ||

| Education | 3.400 | 4.870 |

| (0.550) | ||

| Risk | 0.035 | 0.302 |

| (0.021) | ||

| R2 | 0.41 | 0.31 |

| Price of life saved (in years of wage) | 26.54 | 227.67 |

| Mean weekly wage | 132.65 | 132.65 |

Estimates of compensating differentials

Bonhomme and Jolivet (2009)

Job search frictions: even small costs enough MWP \(\neq\) wage differentials

| Finland | ||

|---|---|---|

| MWP | Wage differentials | |

| Type of work | 0.016 | 0.107 |

| (0.180) | (0.040) | |

| Working conditions | 0.070 | 0.004 |

| (0.080) | (0.030) | |

| Working times | -0.016 | 0.048 |

| (0.070) | (0.040) | |

| Distance to work | 0.162 | -0.031 |

| (0.060) | (0.040) | |

| Job security | 0.537 | 0.068 |

| (0.220) | (0.040) | |

Estimates of compensating differentials

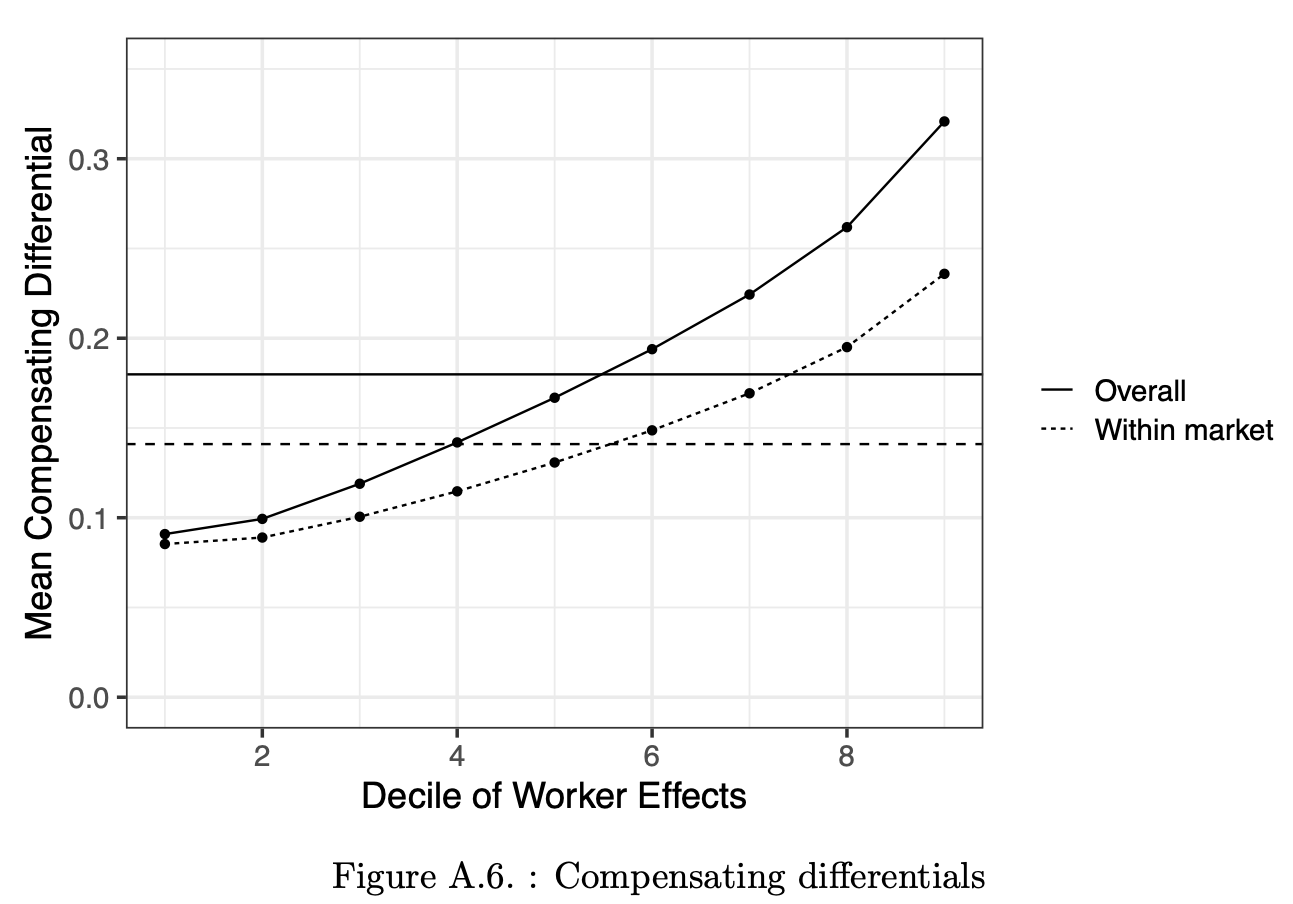

Lamadon, Mogstad, and Setzler (2022)

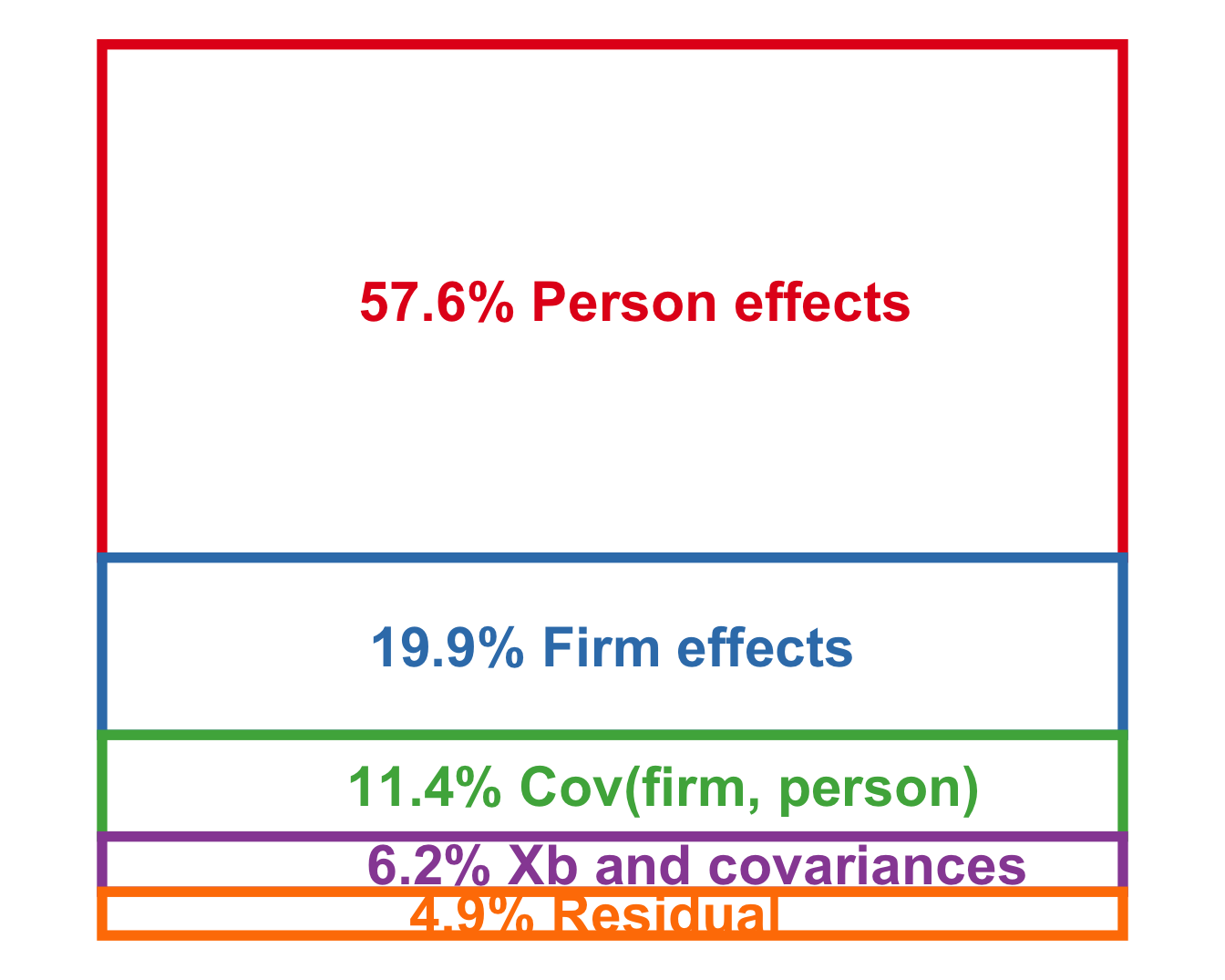

Determinants of wage inequality

Taber and Vejlin (2020)

Estimate importance of four channels of wage heterogeneity:

- Roy model: comparative advantage in skill for job

- Job search model: search and mobility costs

- Compensating differentials model: preferences for non-wage attributes

- Human capital model: boost productivity while working

Determinants of wage inequality

Taber and Vejlin (2020)

| A | Variance |

|---|---|

| Total | 0.104 |

| No learning by doing | 0.096 |

| No monopsony | 0.093 |

| No premarket skill variation across jobs | 0.05 |

| No premarket skill variation at all | 0.008 |

| No search frictions | 0.007 |

| B | Variance |

|---|---|

| Total | 0.104 |

| No learning by doing | 0.096 |

| No monopsony | 0.093 |

| No search frictions | 0.086 |

| No premarket skill variation across jobs | 0.049 |

| No premarket skill variation at all | 0.007 |

| C | Variance |

|---|---|

| Total | 0.104 |

| No learning by doing | 0.096 |

| No monopsony | 0.093 |

| No nonpecuniary aspects of jobs | 0.087 |

| No premarket skill variation across jobs | 0.048 |

| No premarket skill variation at all | 0.006 |

| D | Variance |

|---|---|

| Total | 0.104 |

| No learning by doing | 0.096 |

| No monopsony | 0.093 |

| No nonpecuniary aspects of jobs | 0.087 |

| No search frictions | 0.061 |

| No premarket skill variation across jobs | 0.047 |

Determinants of wage inequality

Firm-specific wage premiums

Firms may pay different wages to otherwise identical workers

\[ Y_{it} = \beta_0 + \boldsymbol{\beta}_1 \mathbf{X}_i + \theta_i + \psi_{J(i)} + \varepsilon_{it} \]

Summary

- Wage dispersion can be related to

- individual heterogeneity in productivity/job tastes

- heterogeneity in job conditions

- monopsonistic employers forcing wage \(\downarrow\) for some workers

- seniority premium with incomplete information and labour market costs

- Incomplete information can also drive most productive workers out

- Differentiating between different channels in data can be challenging

Next lecture: Human Capital on 10 Sep